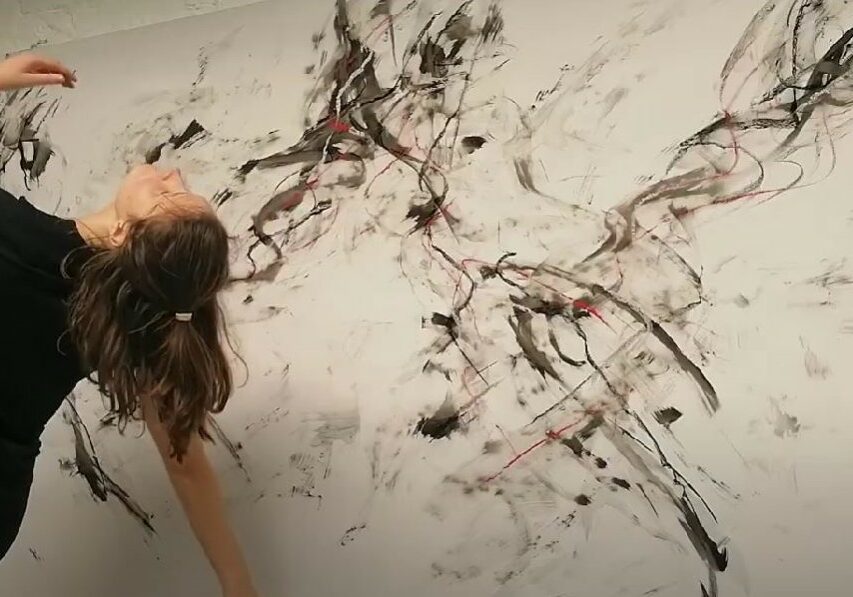

Meet the Artist // Sophia Borowska

I walked into Sophia Borowska’s studio one Sunny Friday, and was greeted by a sewing machine, chair, and table piled high with textile materials. Sophia sat, beaming from her desk, laden with books on architecture and feminist theory and welcomed me into her humble abode, our conversation flowed, reaching into some difficult topics of the past, and predictions of the future. We start with her interest in textiles and femininity.

Your work also looks a lot at architecture, gender and the spaces around us. What inspired you to investigate this idea of gendered space?

I think it came out of starting to learn the engineering of weaving, and then forming a link to architecture, urban space. I came across a short passage by the weaver and theorist Anni Albers that sparked this link in my mind. She wrote about how architecture and weaving are similar in the way that the surface and structure are interdependent on one another. Unlike a painting where you apply something to a surface, in weaving the surface is constructed out of interlacing threads. Structure and decoration are interlinked, and it’s the same thing when designing a building. You have to think of the structure and utility of the building as well as the outside.

In modernism the aim was to strip elements down to their functionality, truth to materials, and that is what I am really interested in I think .

Do you think architecture is quite masculine? And in linking textiles and architecture you are introducing an element of femininity into the male dominated realm?

Yes, if you look at the numbers, architecture is male-dominated, but I don’t want to discount the amazing work that is being achieved by women who have long been working in this field. Many of them are contributing sensitive and interesting work, listening to the community and working together to create new spaces.

Sometimes they have been working and their stories are not getting highlighted in the public discourse, so I like to show it in my work.

How has being in Berlin changed your idea of architecture, compared to the space in Montreal.

Each place I travel to for different projects exists within different contexts. Cities are an amalgamation of the past and present, politics, money, and community. Berlin is one of the richest places to study architecture and urbanism because of its complicated history. Of course some of the old architecture lives on, but most was destroyed in WWII. I think the landscape here really speaks of the changes in government and politics the city has witnessed. Each place I go to has different things to discover.

What do you think it is that attracts you here? Is it the contrast between new and old?

The focus of the project I have been undertaking whilst at GlogauAIR is on the way that the Trümmerfrauen (rubble-women) were clearing out the destroyed buildings after the war. so that’s the contribution of female labour to the rebuilding of the city. They salvaged bricks and construction materials which could be reused, and then whatever couldn’t be salvaged was moved in trucks and trains, creating park hills on what was otherwise a flat city. And to me salvaging architectural materials is the most sustainable thing you can do.

So they were very sustainable.

Yes and they were doing all of this back in the late 40s and 50s. Now salvaging materials, or building for the purpose of reuse is seen as this novelty in architecture, but really it has always been done. Even in ancient Rome . I think it’s really interesting that there is that continuity with building practices.

Now it is cheaper to just knock down and build from scratch. It’s cheap, it’s fast but it’s lost the sustainability that we used to have.

I want to gather some rubble from buildings in Berlin which are being knocked down to make space for these cheap rebuilds, just so I can have this kind of continuity with the past.

A Lot of cities are infiltrated with this kind of rapid consumerism, do you think this affects your work?

Yes, I definitely like to think about the way the flow of the capital and money making decisions are coming into control, and make decisions on behalf of the community.

I mean my Dad’s an architect, and often the main drive for his customers is the bottom line, but for the architect it might be to create and build in accordance with the community.

When you were using building materials, like concrete, combined with yarn and textile materials, were you thinking about gender when you chose to interlink both.

That was one of the early things that I thought about when I was in university. You can really see these two having distinct gendered associations and I think in my work I am trying to hybridise those things and show that it’s not helpful to assign these binary notions of gender.

Doing so prioritises certain things over others. And there is also the hierarchy between craft and architecture, craft is often seen as the lesser art form, and this cute little thing that people do. I am trying to blur all of these lines and shake it up in a jar.

I like that you look at sewing and weaving as architectural , I think this helps blur the lines.

We live our lives in both buildings and textiles, but fashion is not taken as seriously as architecture.

I also wanted to discuss how you use gravity.

A lot of my work uses suspension, and so gravity comes into play. I think it just developed when I started combining all of these different materials and that was what they wanted to do. Using the properties of the materials you have is really something that makes sense to me. Listen to the materials. The construction materials I use are heavy and strong but not flexible, and textiles are flexible and stretchy and can hold alot of weight whilst appearing delicate.

So It is using suspension to highlight the different properties between the different objects.

Right, and if you look at gravity it creates tension. I think the visual metaphor of tension says a lot without having to explain anything. There is an exchange of weight that is happening which makes the installation the way that it is. There is also this element of danger, especially when something as dense as a brick is suspended. I like to play with the properties of materials, how they relate to each other and how they relate to their environment.

Who are some people who influence you?

I mean, Anni Albers, and another of my favourite artists, Eva Hesse were early influences. Also architects like Eileen Grey and the collective. I enjoy process driven work. I follow this collaboration between myself and the materials to see where the project is going. I don’t think that I have a really wild imagination, I just like to slowly discover things. That is why I like to visit cities, have my feet on the ground and experience spaces.

What have you enjoyed doing whilst in Berlin, what has really influenced you in the city?

I love visiting all of these rubble hills, and walking them, seeing them, observing the pieces of old bunkers just sticking out of the earth.

I like to sit with it and feel, really try and understand what it feels like to bury your history in this way. It’s such an interesting and intense thing for a city to do, especially when the women are the ones who were doing the lifting and labour.

After the war there weren’t many resources, so, in order to get their ration cards women had to do rubble clearance..

Those material shortages are something I want to talk about in this project, because not only were there housing shortages but there were these clothing shortages as well. Women had to re-use old army uniforms, blankets, curtains, rags, and whatever they could find to keep families warm. There was also this element of criminality, as things were being sold at inflated prices on the black market, so they had to navigate this as well.

Yes, and the war was such an interesting subversion of gender, I mean, without the men it was the women left to replace them, and I think people often forget that.

And I think, from what I am reading, when the men came back they kind of wanted to return to their previous power, and women were just not having this anymore. In the German context it is also more complicated because they were responsible for the holocaust and all of the atrocities, so it can be hard to completely empathise with the hardships German people also endured. Of course, being in the country does not mean they believe in the politics, and a lot of them were under duress but it can still be challenging. I have to always keep that in mind.

It is so heavy, and so many spaces continue to carry these feelings, the weight and the legacy.

Yes, and you can read about it and learn about it, but you don’t really feel the heaviness until you are in these spaces I think.

Also, what needs to be addressed is not just remembering that these atrocities happened, but realising that they continue to happen in places throughout the world. Those heavy spaces are being created right now, as we speak.

And finally, what is one Pivotal moment that has happened to you so far?

I was 12 when I went to the Gobelins workshop in Paris and watched these weavers, and we left and I said to my parents, I’d like to do that. I think that was a transformative moment, and my family has been very supportive of me pursuing this path.

*

Website:https://www.sophiaborowska.com/

Instagram: @sophiaborrowska