My project for the residency at GlogauAIR approaches the unraveling of time by thinking with and through the metabolism of algae, in order to engage human knowledge and research with other forms of life.

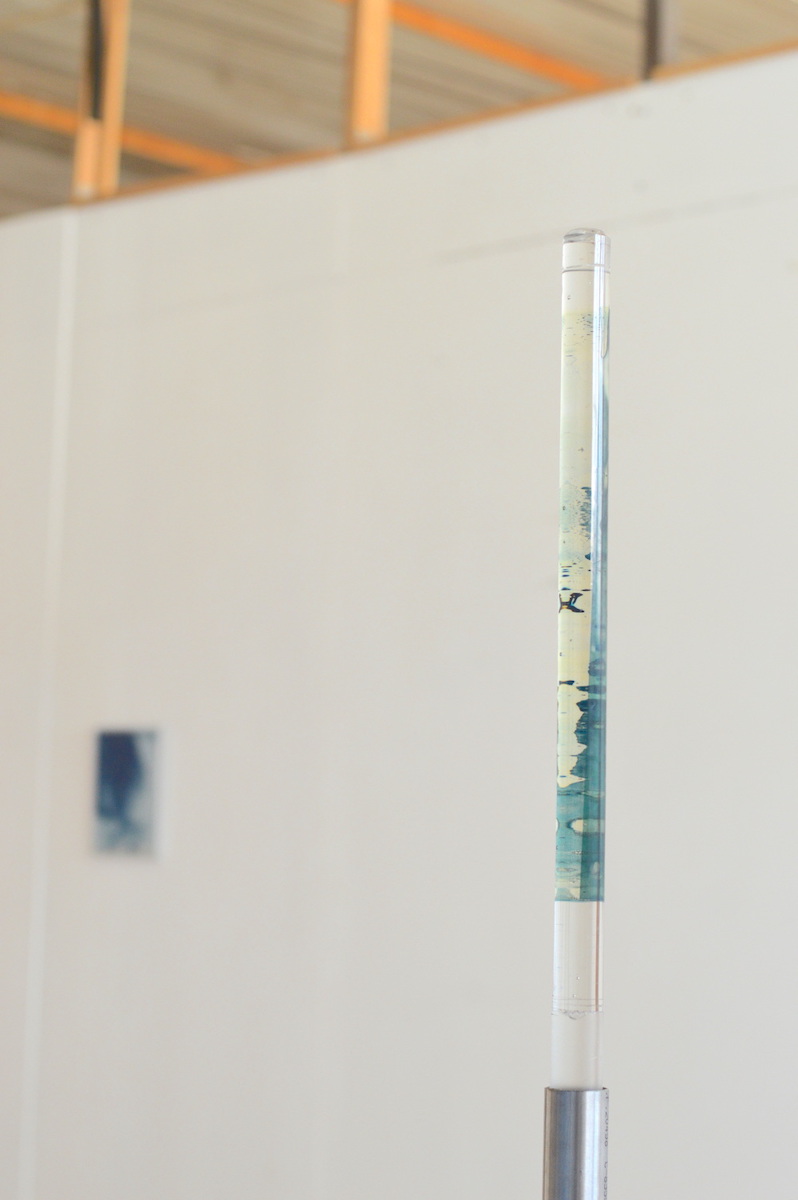

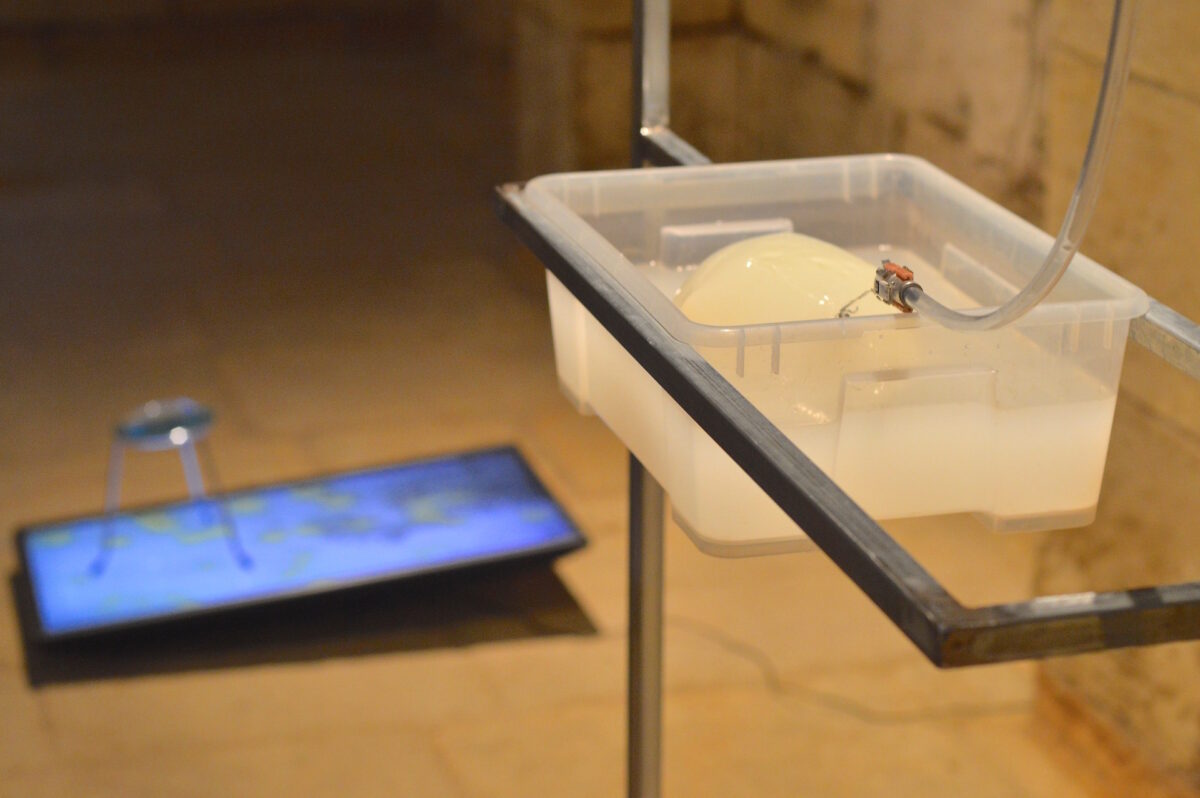

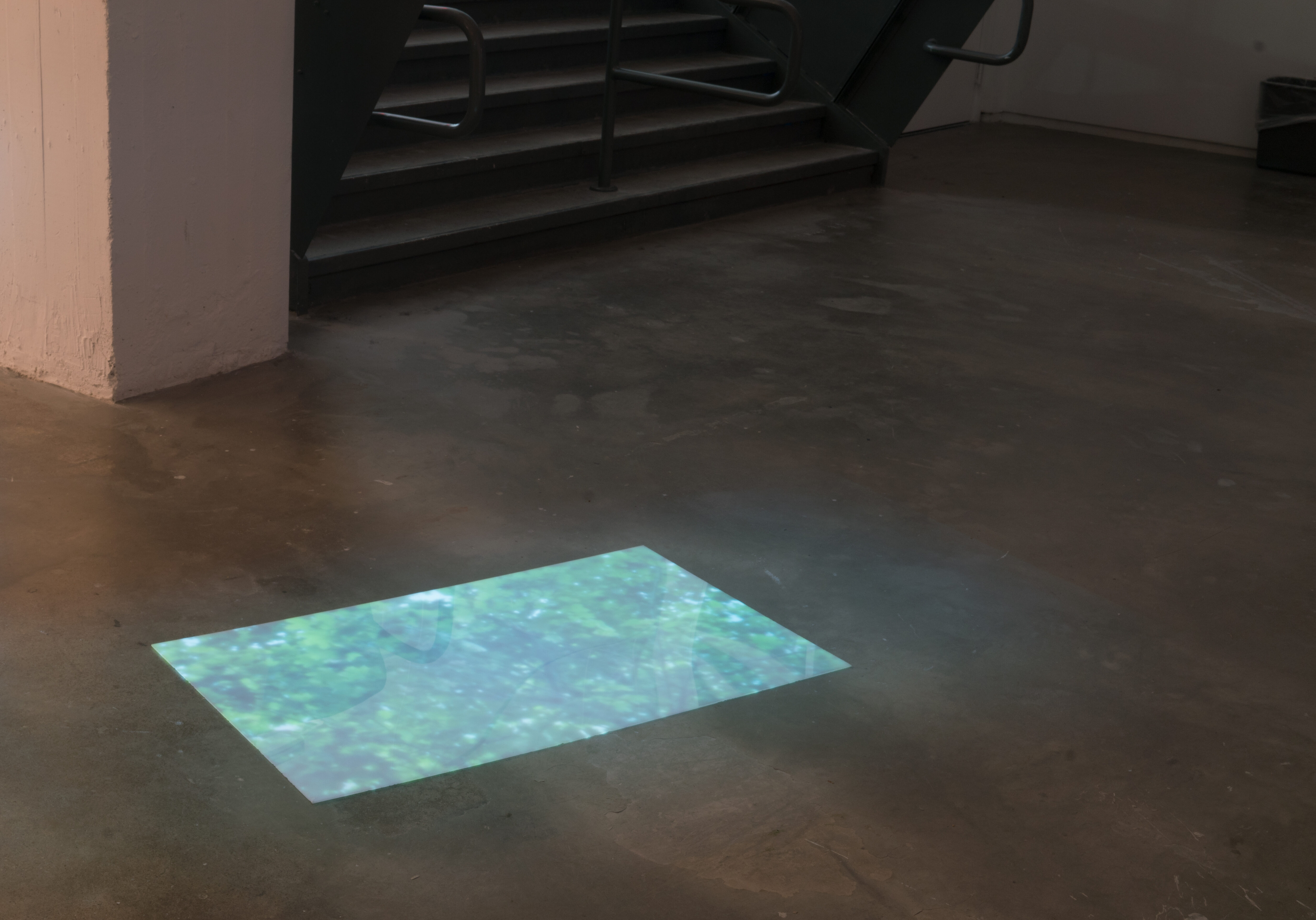

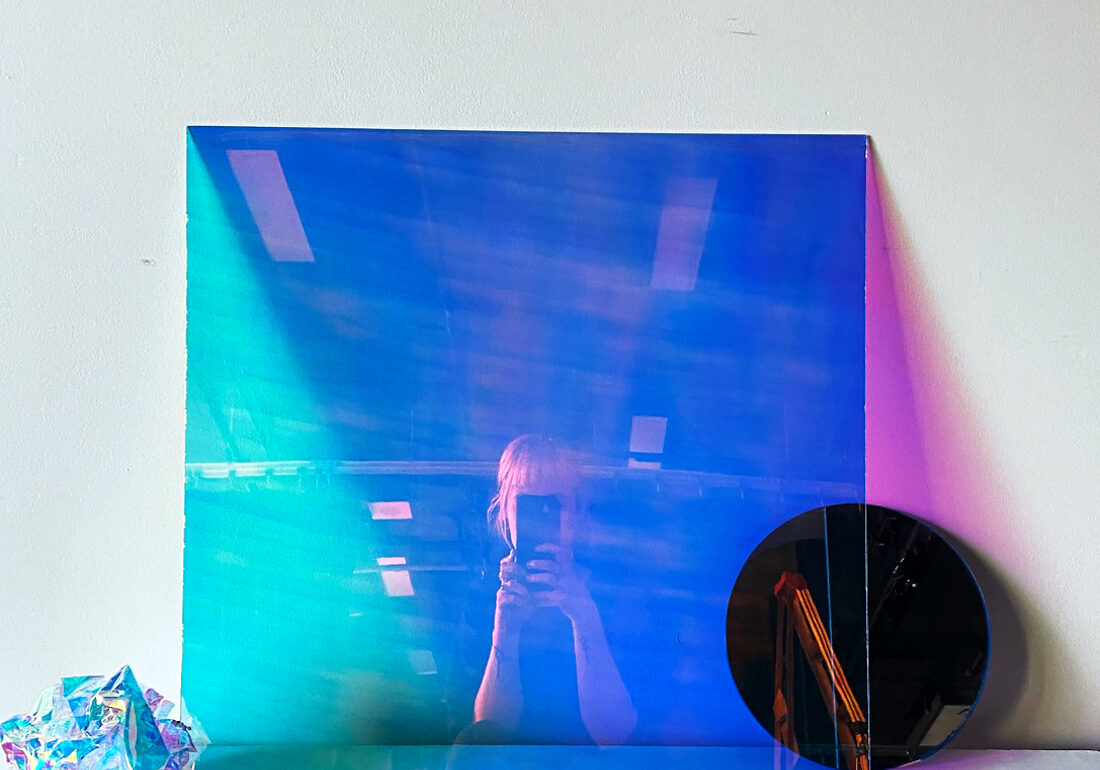

I have been experimenting with agar-agar (a type of algae) as a substance that needs tending to ‒ being somewhat alive, the sculptures must be submerged or require constant hydration in order to avoid drying, or drying can be encouraged altogether, pushing the material further to its physical limits. In any case, it is a material that welcomes nurturing and displays a kind of transient fragility that I deliberately explore. This perceived thirst of the material is picked up as an incentive for installations that operate as part hydration system, part assistance device, attempting to maintain the sculptures moist and therefore intact.

Thus, the notion of unraveling time comes into play as an unraveling system – at once formal and biological – through which fluids are activated, absorbed, modified, affected, transported and ultimately, transformed. As such, the dynamic vitality of algae would constitute the material basis of a system beyond the human scale, while simultaneously provoking intimate associations with our own physiological processes.

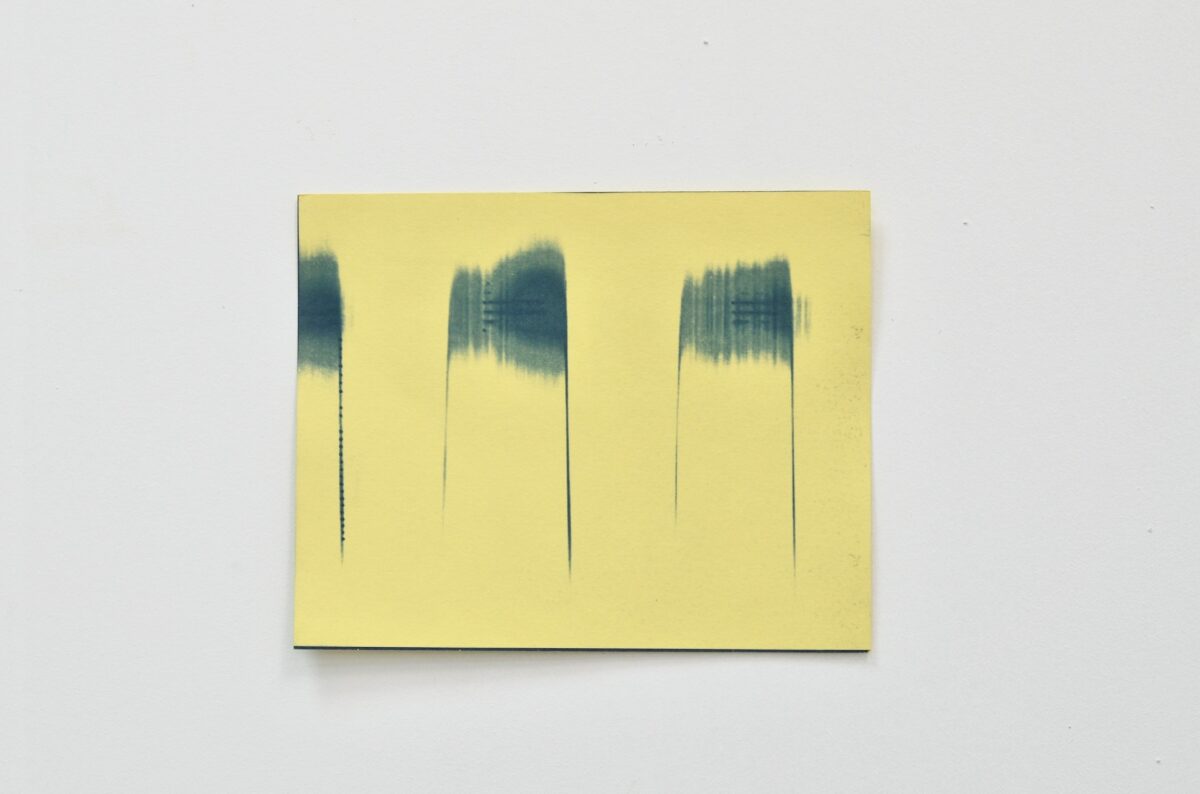

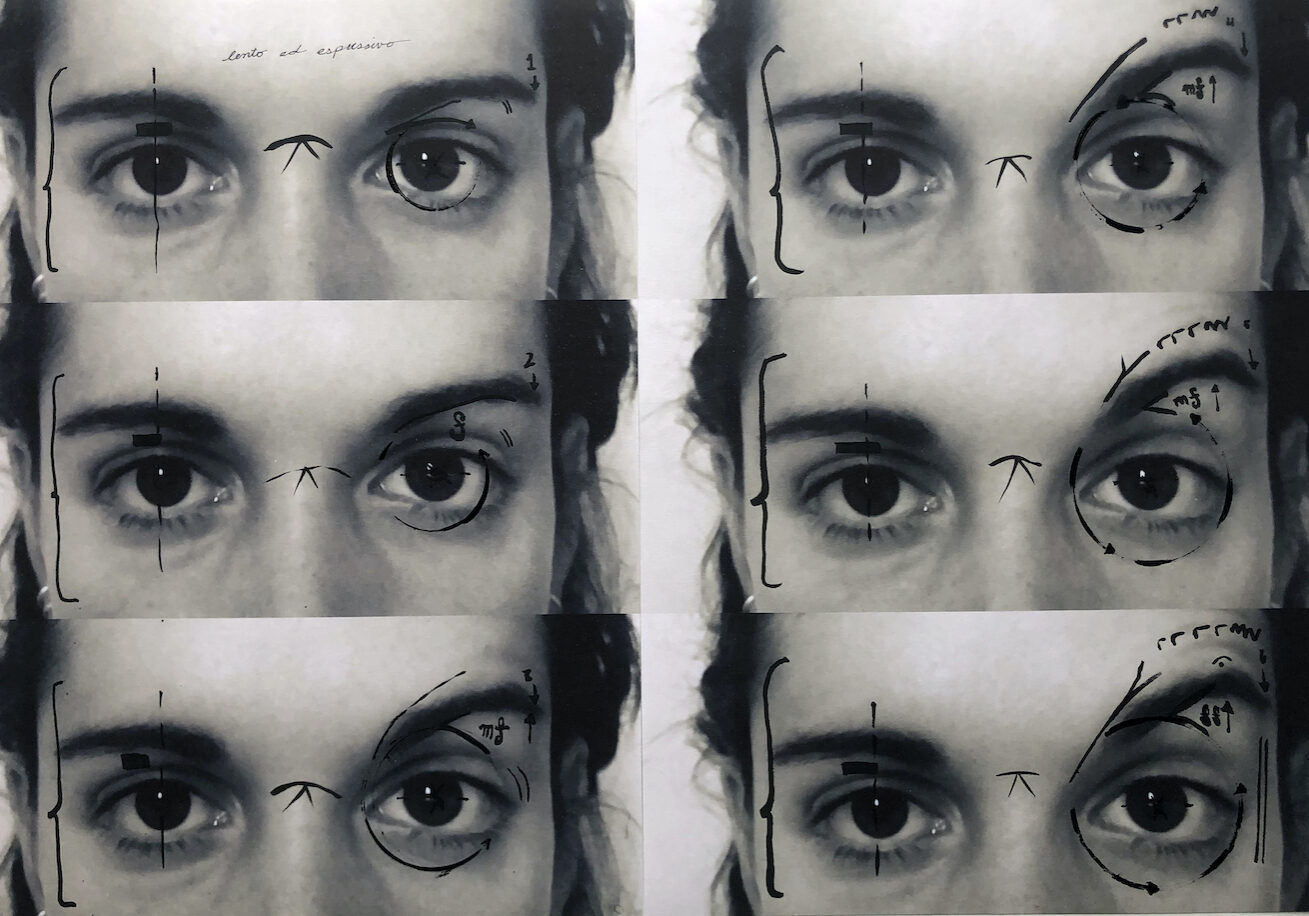

This material investigation would be anchored in the universe of Uromancia, an ancient technqiue of ‘’reading’’ urine, prevalent during the advent of uroscopy, in the early 15th century. The science of looking at the urine for diagnostic purposes is as ancient as disease. Throughout history, urine, the first bodily fluid to be examined, has continuously and persistently provided medicine with an increasing body of knowledge about the workings of the inner body. For most of its history, uroscopy was a visual science; this focus peaked in the Middle Ages, when the vessel used to examine urine, the matula, became a symbol of the medical profession. Over time, the practice of uroscopy spread into the hands of quacks and apothecaries, who prescribed and sold their potions by merely looking at the urine. The consequent reformation measures of the 16th and 17th centuries coincided with the first attempts at analyzing the contents of urine. As a result, many of the chemical components now reported in metabolic profiles were first analyzed and identified in urine during the first half of the 18th century. In the process, what started as a science that bordered on divination laid the foundations for the anatomical understanding of the body we have today.

Thus, actions performed by our bodily systems responsible for processing water and balancing its levels in the human body, would be reenacted outside the body through the gellatinous and highly absorbant qualities of certain algae.