Meet the Artist // Ollie Kendrick

Ollie Kendrick is a multi-disciplinary artist from the UK and his work uses both still and moving image to explore the image spaces around the concept of boredom. His method of artistic research incorporates psycho-geography as a main element in the image-making process, mapping a collection of objects to psychoanalyse the psychology and the inherent psychosis of the urban landscape.

Can you tell me about your background and the project you’re proposing for this three-month residency here at GlogauAIR?

Originally, I’m from Wolverhampton in the United Kingdom but I left when I was 18 and then spent the last 10 years mostly in London. I went to art school there and finished just over a year ago. The project I’m proposing to do here is related to my hometown Wolverhampton and also related to the work I’ve been doing recently around boredom and grief. Specifically, their relationship towards not just architecture but industrial objects and industrial and post-industrial landscapes.

Originally, I’m from Wolverhampton in the United Kingdom but I left when I was 18 and then spent the last 10 years mostly in London. I went to art school there and finished just over a year ago. The project I’m proposing to do here is related to my hometown Wolverhampton and also related to the work I’ve been doing recently around boredom and grief. Specifically, their relationship towards not just architecture but industrial objects and industrial and post-industrial landscapes.

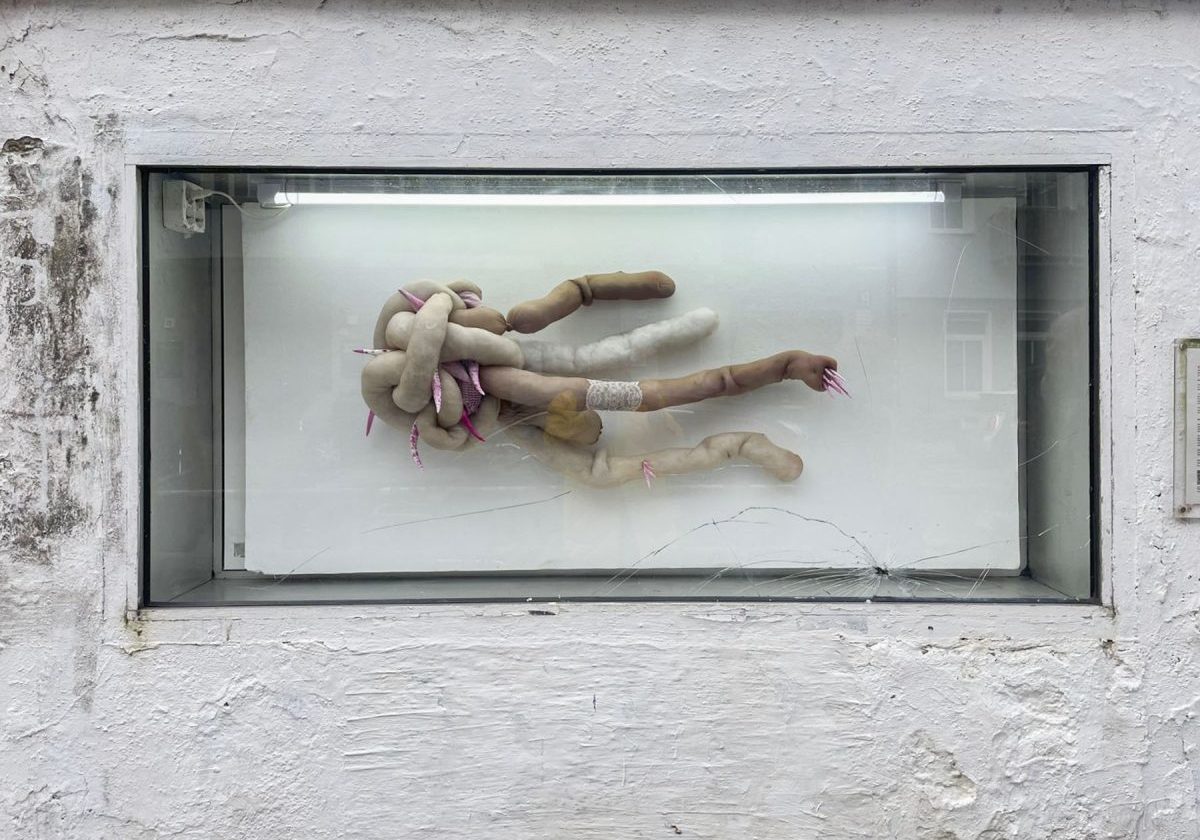

The project I’m proposing is a mixture of installation specifically using objects that are related to industrial forms of production. I’m using PVC curtains to express the emotion of grief, and working with objects to see how they communicate this emotion. Also, I’m using objects that are related to my hometown, such as rubber and tires. I’m thinking about how the emotion of grief might be connected with my past work of boredom through combining the new digital contemporary landscapes we live in and the more recent past of post-industrial and industrial landscapes. So, using the objects to bridge that gap or have a dialogue between those two things.

How do the sculptural and photographic processes interact in your work and what is the relationship between the two in the materialisation of your project?

With the process of film development I’m trying to think about how that interacts with the idea of boredom or my relationship to boredom. The process of developing photography and having connections that are fundamentally detached and separated from the way we interact in the virtual space and digital space, how we interact with digital images. They’re instantly shared, liked or interacted with.

Film photography is a whole other process that actually runs parallel to the experience of meeting someone, of exposing them and discovering their personality. I guess that’s really the idea behind portraiture. And that’s been interesting: trying, through my work at GlogauAIR -and actually even before I came to GlogauAIR- to figure out how to capture those photos, that moment I just described, and how to combine it with these very cold, industrial materials like aluminium, and also with resin.

Those materials are interesting to me, resin specifically, transparent resin, because on an aesthetic level, it’s as if the digital screen is liquefied and then kind of re-solidified. There is this kind of digital transgression to me in some way or movement with the liquid and you can kind of distill things and trap them.

I’m working with aluminium as well. I’m interested in its relationship to modern structures, and how it connects to modern architecture. That’s something there in the context of my broader work with architectural film. There’s a coldness to it, it’s very reflective, very clean.

I’m especially focused on how to combine photography with these modern objects and materials in a way that creates a dialogue between the digital and the filmic. It’s about saying something about the modes of being, that nowadays, feel so fast and transactional. How can I work with that tension between the slow, organic process of film development and the act of meeting people.

That’s how the ideas are trying to materialise through objects. With the PVC, that’s more recent, I’m using the performance of drip painting, trying to perform grief on an industrial object that has the image of an erased space of redeveloped post-industrial areas from Wolverhampton. Is interesting because it’s combining something that is very vulnerable and emotional with the colour and the painting, with this very industrial object of transparent PVC.

Showing the work from the other side of the painting is interesting to me in terms of how grief can be communicated, a very vulnerable and difficult emotion that is seen as something that’s traditionally hard, you know, like labour and producing, you can then even talk about the way in which emotions in working class communities are much less experienced or, not experienced but expressed. So, that dialogue is quite interesting.

You refer to psychogeography as a fundamental part of your process. How do you apply this methodology when capturing images or selecting objects?

In terms of collecting images, it’s related to the idea of the flaneur, which evolved in the 19th century and a type of movement through urban spaces where one follows and ultimately gets lost in the city and its crowds whilst following different energies.

There is an inherent idea of people responding to their environments, and the environments themselves, therefore, are imbued with a special energy. So, taking that idea and then seeking out places where actually there once was this energy, also trying to feel that retrospectively is how I use psychogeography. I mean, if psychogeography is the idea of mapping the psychology of space, or maybe even the psychosis of space, if you think about how a city like London -how random and almost neurotic- but the way in which it’s built, the way in which its history is layered.

What I’ve tried to do is, when you’re using psychogeography you’re also mapping history, as well geographical history. So, I’m using psychogeography to map my own experience of life through time and space, and coming from a filmmaking background, gathering images in a way that I find very inspiring, specifically in the context of Patrick Keiller’s work, who is a big influence of mine. He uses psychogeography in his film practice, as a way to release the surrealism of a realist image.

So, if you’re taking, for example, the image I’m working with of the Goodyear tyre factory in Wolverhampton, how can I use objects and artistic practices to unleash the surrealism that I feel around this space? So, what’s really interesting about his work is these fixed shots in which there is a narrator narrating an absent protagonist. And in that, through that structure and movement of the absent protagonist through space, you’re creating the surrealism which I guess is tied up in the history of the shots of the places that are captured.

I’m trying to kind of use that in the same way, in terms of how I work with the objects. Trying to bring this surrealism through a realist image.

In what ways does Berlin’s urban environment influence the project you’re developing during your GlogauAIR residency?

I guess I get the same feelings of dread in the areas of former industry, especially where it’s not even post-industrial, I guess it was industrial, but it’s now just logistical centres, where goods are moved to and from. So, DHL and UPS and things like that, Amazon warehouses. That is interesting to me, because there’s a special type of absence there, in which it is just pure space of transience and movement of prefabricated goods and objects. And so that kind of dread of erasure and empty space that is embodied in this type of industry that is predicated on increasingly fast and disposable commodity production and consumption. So I guess this is the way in which capitalism reanimates space into increasingly homogenous types of architecture, faceless warehouses with bright colours

I find taking walks in places like these, feeling the lack of lived-in-ness and lack of energy of people there. I find that really interesting, that feeling of dread, which I also get when I go back to Wolverhampton. But that’s different, because I have a personal relationship with that city. With Berlin not so much. I think the way in which Berlin is changing and how it redeveloped its industrial spaces is very interesting to me. The way identity can move through space here more freely, the need to remonetise space is less urgent here than the UK, so there is more space for artists both culturally and mentally.