Meet the Artist // Esteban Patino

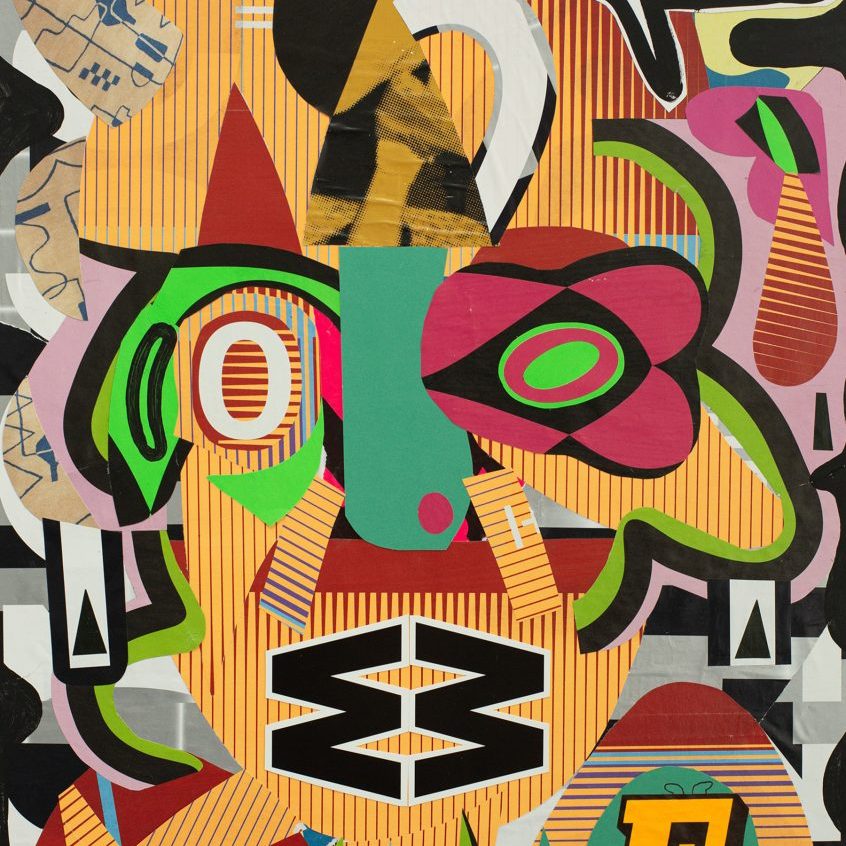

Esteban Patino’s work delves into language creation and perception through sculpture, collage, and painting. Using a self-designed 24-character symbolic system, he explores the illusion of language and its structures. Sculptures focus on universal, timeless shapes; collages depict humanoid forms reflecting existence’s complexities; and paintings bring intuitive, mythical entities to life. These distinct styles interconnect, examining words as symbols with infinite interpretations and the human mark on our world.

Patino’s GlogauAIR project will explore the universal power of symbols and visual language, inspired by ancient cave paintings, modern pictographs, and timeless shapes that transcend eras. Through painting, collage, and sculpture, Patino aims to create a unified body of work that engages the public, fostering a message of shared humanity and connection. The project investigates the essence of universal comprehension, using art as a timeless code for communication to inspire unity, innovation, and trust.

Can you give us a bit of an introduction to you and your background?

I was born in Medellín, Colombia. When I was a kid, I liked art. I used to draw a lot. When I was about 16, I went to an art academy – an uncle was the one that got me into it. So I started classical drawing and classical painting at the same time that I was going to high school, because you could do that back then, and this is in Colombia. When I finished high school, I went to a university for art for one year, and then my dad and I moved to the United States.

We moved in 2001 or so, and then for a while, I didn’t do much art. Finally, I moved to Atlanta, Georgia from Florida. When I got to Atlanta, as a coincidence, I went to a warehouse where other artists were doing work. A friend of mine got me a studio there, and I started making work and meeting people, getting into the art scene, the art world. That became kind of like my home and where I do my work. So Atlanta’s home. I’ve been there for 24 years at this point.

So you started with a more classical sort of drawing – how would you say your interest in symbolic language began?

When I was studying more classical things in school, I was most interested in Surrealism and things like that. It was the Surrealists that were using symbols to decode the human psyche. They were using automatic drawing and things like intuition, more than really looking at [physical] things.

I don’t remember exactly what sparked it, but somehow I got interested in universal shapes or almost cave painting – just things that humans started doing by intuition or painting images that were so basic, like a hand or an animal. It was universal. And so when I was doing the classical drawings and paintings and learning more about art history, I started focusing on Surrealism. I started focusing more on what I felt would be immediate. Also, I’ve always liked anthropology and the study of humans – why we came up with society and structure and language. There was a point where I was doing paintings, using more bodies or shapes, very graphic. And then, since I was interested in language, I kind of started breaking those forms apart, making my own symbols to play with – not so much to write things with my shapes, but to play with abstract forms.

I don’t know exactly where it’s going when I start – I just start putting things together, and then some shapes or forms or entities come up. So it’s a very intuitive process.

So it’s a sort of primitive kind of interest.

Yes, primitive. And what they call Art Brut, right? But also with some background and investigation – investigation into art history and contemporary art. So you have to be informed a little bit of what’s happening around you, with some knowledge of the past, and then you go in with your style or your technique.

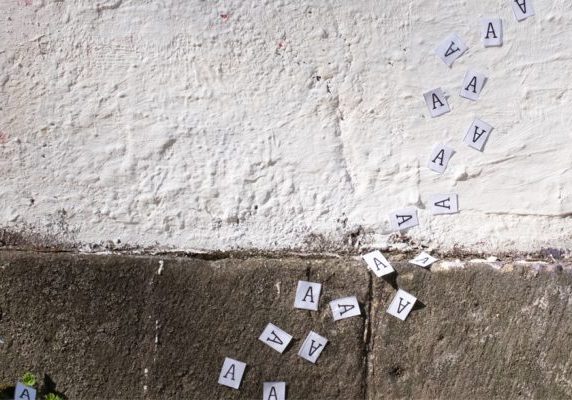

I do like some of the Art Brut artists – they were really repetitive, which is something that I like to do in my work. With the language, the alphabet that I sometimes work with, or with the shapes that I’m using right now – with stencils. I don’t really sketch much but I do build on what I’m doing. The piece informs me of where it should go, instead of having a set on this work. On the sculptural work, which is more with my alphabet pieces or with my tool set, then I do have an agenda, and I do know what it’s going to be, because they’re made out of steel. That’s more conscious.

Regarding your paintings – is there anything you consciously start with, besides the alphabet? Or do you just let your intuition guide it?

When I started here at GlogauAIR, I did have a background and a plan. I do have a few set of guidelines, but then I break them. In one piece, it was going to be two colors only, and then I ended up with three – the orange, the blue and the gray. So those rules were meant to be broken, right? And it was just a coincidence – I ran out of orange.

You do have to have some rules so you’re not all over the place or not knowing where to start, but then you get to a point where you say, okay, now I’m going to break some rules. Otherwise, it’s kind of like you’re getting in your head too much.

How do you think your practice is changing or developing?

It’s funny – when I started working with the alphabet pieces, I wanted to work with representing language, working with text, and then that became sculpture, which became more random abstraction. I am very aware of when it stops giving me what I want, then I’ll drop it. My work is not like that phrase ‘’one-trick pony’’ – my body of work may seem similar in a way, but it’s very broad.

There were ones that I did with a background behind that was the same letter repeating itself. Adding the black shapes started within the last four or five months before coming here, and it was the perfect excuse to explore that more here, instead of what I did last time, which was collage. I’m finding things as I go, as well.

Infinite possibilities.

Language, especially. It’s always developing, and you can always find a new aspect to it. That’s what we are as humans – that is my fascination. Every culture just came up with some little shapes – they’re so different, but they used them to communicate. I thought, I want to do something like that. I want to create my own little shape, and use it to communicate abstract painting, or other things like that. And you don’t have to know exactly what it is. If you know all the answers, then what’s the point, right?

What are your plans for after this residency?

I’ll go back to Atlanta, but I have a project, which is starting a residency in the mountains of Colombia. There’s a big coffee farm there that an uncle owns – the same uncle that started my art career – and I want to set up a small residency for five artists. I want to see if that’s a possibility.

If not, if it’s too much for me to do, then I’ll just go and paint for a couple of months in the mountains. I’m an artist, you know, but I can be more than one thing. I think it’s just the timing of it all. I still want to do more with the paintings.

How do you come up with the ideas for the stencils? Is that conscious?

No, not at all. I’m just creating fun shapes, and universal images. The hand, of course, is very easy. That’s why it’s in the first piece I did here, because I needed to start with something.

I want these paintings to look like it could be done by anybody in any country. You know, I don’t mind if it has a South American look, but I don’t define myself as a Colombian artist. I’m just an artist. Certain things are so universal, like this stencil of a hand I’ve been using. It’s basic, but universal … there’s an idea that we can all do it.

Is Berlin inspiring you in any way, when it comes to the shapes and your intuition?

I do let it filter through the work, because I’m here, you know. Some people, they bring what they do and they keep repeating what they do, but I think if we’re here we should let it come through. There’s another month and a half, so we’ll see.

There’s one painting that started to look like birds flying away, and there are a lot of birds and those sounds around here. And there’s a blue and orange one I was working on, and just finished a couple of days ago – to me, it looks like an owl, so I named it Night Owl. Because in Berlin, you go out a lot, and you stay out really late. And you start seeing things that aren’t there.