Meet the Artist // Liang He

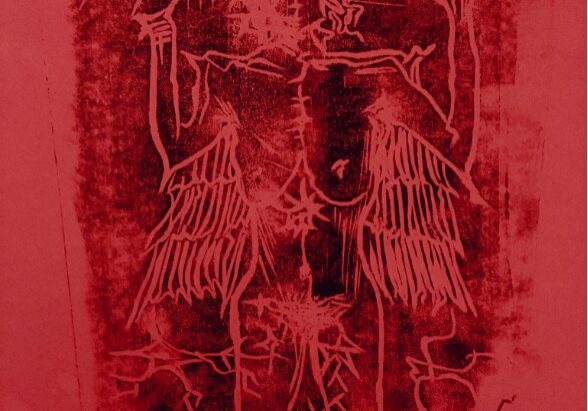

Liang He is an interdisciplinary artist, researcher, and gamer. He creates sculpture, installation, and cartography to replicate, and counterbalance anxiety concerning human subjectivity under capitalism. His research focuses on discourse around domination, delving into political, spiritual, physical and technological violence surrounding drones, cyborg, and cold war bunker.

Can you give us an introduction to yourself and your background?

I’m currently taking a gap year from my MFA, which I’m doing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. I study art in the art and technology department. I also went to undergrad in the same school, where I focused more on photography and sculpture. Video games and play has become a central focus of my practice for the past few years. They have shifted from more of my hobby to a research focus which drives my artistic practice.

So over the course of the past year, you turned it from a hobby to a career.

Yeah. I’m trying to find a practice that would make sense for my life, and a practice that can be sustainable for both my mental health and also from an economic standpoint. It has been a big shift, because I figured that in order to make art for the next ten years at least, I have to find something that I really enjoy doing.

Are video games where your interest in machines began, or did you always have that interest?

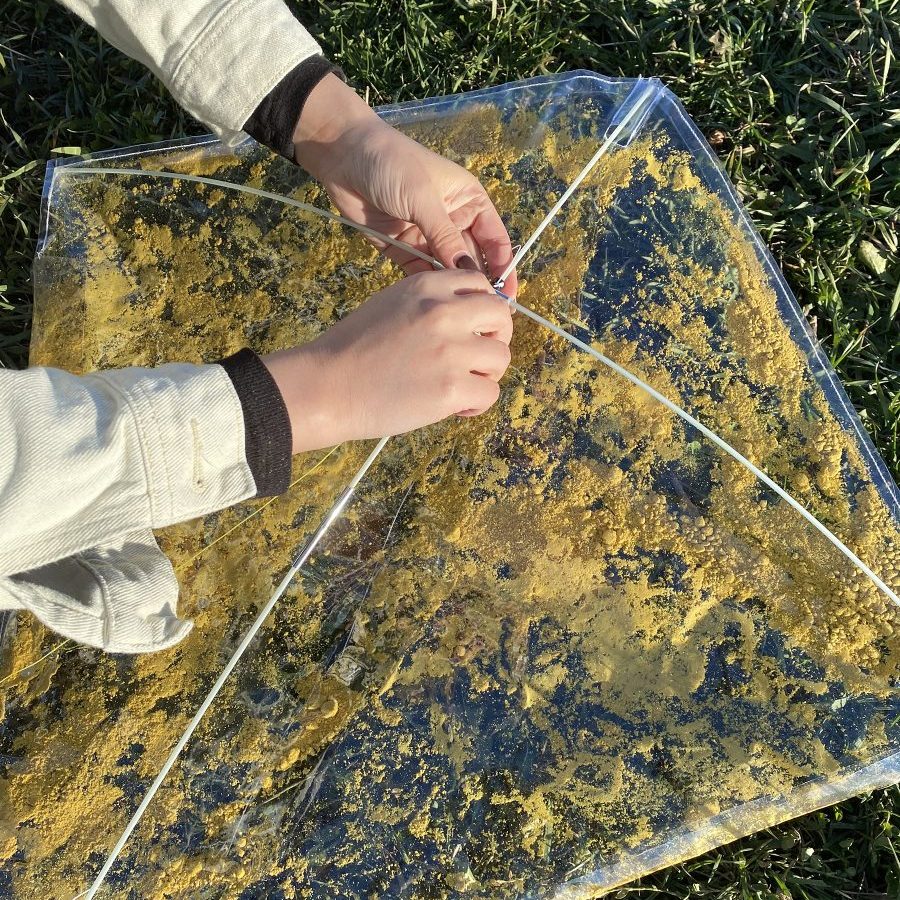

When I look at the history of video games and computer genealogy, they overlap hugely, so that’s a part of it. But, my interest in video games led me to want to be playful within all the elements that I would use in my practice, no matter what it is. When it comes to machines, it’s reassembling, hacking, and just appropriating and repositioning the narrative to somewhere that they are originally not, hoping to poke at something relevant to ideas in our time.

I’m thinking about this quote by Felix Katari, and I’ll narrate it in my own words, he talks about the experience of watching television and when you’re watching it, you are first kept by this materiality of the television – the pixels, the light, the sound, and everything, the physical enjoyment – and then secondly, the narrative content of it – maybe it’s talking about an advertisement, maybe the news. And then the third – your fantasies, what’s going on in your mind, your daydreams. And then it’s along with your surroundings and what’s going on in your environment, like water boiling, music, ambulances. That kind of stuff is what draws my interest to human machines – this complicated experience of our lives, while living amongst machines. It’s all tangled together, and I want to recreate that in my artwork.

Whenever I use a machine in the artwork, I’m trying to refer to both the literal sense of a machine, that’s functional, and how it engages with you. Also, how it leads to this broader relationship of ourselves with the system.

Do you foresee a world, maybe 20 or 30 years from now, where it’s so integrated that we can’t even tell the difference between a virtual world and a non virtual world?

In 20 years, I’m not optimistic about it. I saw an artwork recently – it was an NFT, and the artists built a big sandbox, kind of like a city, with all these building parts, and you can register your own robot in that city. They created a whole virtual system to simulate the robot’s life – they have an economy, they have a day job, they have to work and rest like us.

They start a family, and their children become NFTs, and it goes on forever. I think that’s a very good metaphor for our future.

I’m reading a book right now on the conscious machine, and I’ve just reached a point where they are talking about building a robot that is conscious, that has its own subjectivity and their own thinking. It’s really interesting to see how far we’ve come from what we set out to do in the 60s, when the study of AI was just starting. Right now, our models can only understand language, and they predict what you say based on the data that is used to train them. So actually, back then they predicted that nowadays we would have had more sophisticated machinery. It’s completely possible and it shouldn’t be hard, in theory. We have machines that can calculate as long as we give it the right input, but the problem is how long it’s taking. It could take forever.

Another problem we need to work on – we need more data. You really need thousands of millions of this kind of data in order to make a machine sufficient enough.

They have been processing data through a technology called neural network, which is a network of computational unit that try to mimic our brain. We’re also constrained by brain science – we don’t fully understand our brain yet.

About computers taking human jobs, it’s not something that will happen soon, because computers are just not far enough. People should learn to use AI like everybody else – it’s become a part of many jobs, helping with certain tasks, especially as it relates to language and translation coding and writing. We have machine arms, which can be their physical agency, but they are far less sophisticated. With AI for writing, I use it for making the writing more accessible to different levels of audiences. So the jobs have just changed, right? But it’s not going to disappear.

It’s like a thinking partner. You brainstorm with it.

We’re always so worried we’re going to get replaced, but I don’t think that will actually happen with machines. That’s one thing that I’m studying – I’m trying to create my own history and alternative computer history, but one that’s specifically related to subjectivity. As a machine, it’s there to serve as an instrument, and I think it’s very interesting how we have been developing this dynamic. Sometimes the machine processes more knowledge than humans when we ask them for help, but in turn we as humans are processing knowledge with feelings. There’s always going to be some sort of benefit that people will see with machine integration, and machines as liberation tools, for example, with disabled people.

With myself as an artist, I can now use these tools to generate imagery, generating 3D models, which would really save me a lot of money and work if I can invest in it. The problem is when our government and capitalist system has applied this technology as a force of control. There’s the good and the bad. Facial recognition technology, for example, is not the problem per se, but it’s how people and governments apply it. If it’s properly decentralized, and machines don’t fall into the wrong hands, and it can be used more liberally by common people, then it can do good.