Meet the Artist // Abigail Severance

Abigail Severance is a Los Angeles-based artist creating films and images that explore nostalgia, flawed history, and queer thought. Her richly composed, meditative works blend documentary, fiction, and abstraction, reflecting on post-pandemic fragility, entropy, and queer futurity. Through sensory imagery, she examines time’s impermanence as a form of witnessing, offering both refuge and a space for imagining radical possibilities.

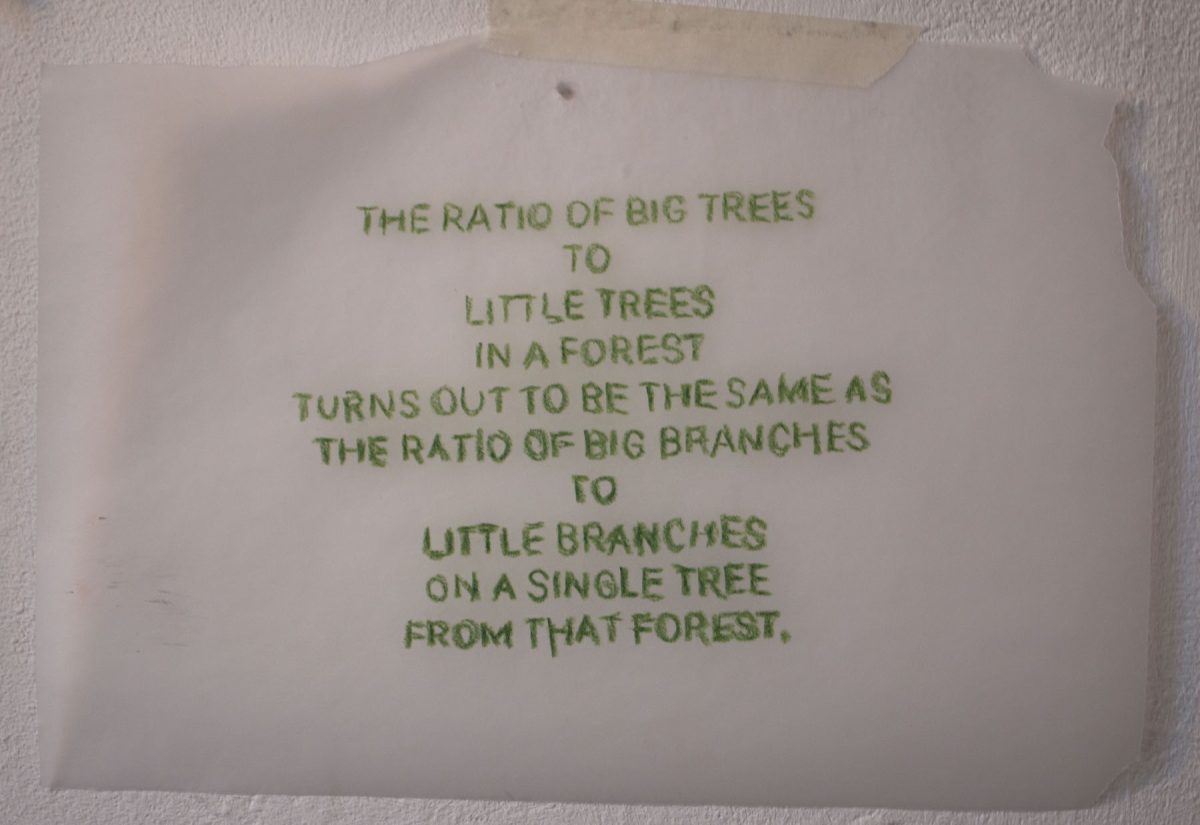

Can you describe a little bit about these tree visuals on your wall?

This passage is from Brian Enquist, in Katie Holden’s amazing book “About Trees,” which is a real north star for me right now. He says “The ratio of big trees to little trees in a forest turns out to be the same as the ratio of big branches to little branches on a single tree from that forest.” And we’re not talking about a cultivated forest, right? Because if you walk around Berlin, you’ll see that they trim the trees back, and there’s all these tiny branches that wouldn’t be there organically. But in an organic forest that’s not being managed, or at least it’s not having its branches trimmed, a single tree is a dimensional representation of the entire forest. It’s a fractal. Apparently, according to Enquist, Leonardo da Vinci was the first one to observe this relational thing about trees, that the circumference of a tree’s branches corresponds to the ratio of big to little trees.

I’ve been working through this idea of an individual human being as an archive – a collection of senses, experiences, losses and surprises – and we apply that archive to everything we encounter. We are also fractals that relate to things. The Hindu idea of the eternal return says something about fractals too: There’s an infinite world inside every human and then an infinite world inside that world, right? There’s all of this remarkable science about how trees warn one another about viruses or infestations. Trees figure out how to help each other. And I just think we have so much to learn from that.

And how arrogant we’ve been, right? To think that we’re the species that is the most sophisticated, the most advanced. I think that conversation’s changing. That’s one of the things I’m really interested in: what models for cooperative living are offered by non-human systems? I think this is deeply related to queer models of futurity, too.

I think a lot about how softly “the apocalypse” (as if there will be only one) will come, how slow and quiet it will feel until it is everywhere. And I think about what we might draw from radical queer thought, particularly José Muñoz’s provocation to inhabit and express queerness as a broad social challenge, not just an identity but a position. Maybe it’s the radical queers that will show us the way through the end of this human world. Most of us already invented ourselves out of nothing, so you know we’re imaginative.

Here in Berlin, I’ve been experimenting with moving image and sound that can provoke thought around this idea of how to face the apocalypse, the possibilities offered by other threatened systems, models we might look to as the Anthropocene comes to an end. I’m not interested in making a documentary or even an essay film that explicitly says these things, but the reading and the research on natural systems like forests, glaciers, oceans is really informing how I’m shooting and listening here. So I can make something where this idea is felt, sensed.

Can you talk about some themes in your recent work – changing cities, resistance of marginalised bodies, and the ‘’intertwined viruses of capital, COVID, and climate’?

During the pandemic, we had a really useful thought exercise put in front of us – a disastrous thought exercise, which was: what if we do this differently? Clearly we can. We can shut

down the world and try at least to protect people, right? We fought about it, and made stupid political moves over it, and stupid economic and capitalist moves over it. But our focus was on recovery, economic recovery, social recovery. In a general sense, I think when the story is told of this time, it will be one of recovery. Which is too bad because we could have experimented much more with how to live differently on a global scale.

Our studio visit yesterday brought up the word rewilding – this idea of either encouraging, actively helping or allowing a place to be taken over by nature, or retaken by nature. I like that idea, that we have a role to play… mostly we can get out of the way, let things deteriorate or regenerate. What if this were an intentional stewarding process, to agree to and enable entropy?

And I’ve been obsessed with trains! As an American in Europe, it feels very novel to travel by train so much. Maybe they are also an example of systems we can learn from. A train is both soothing and sinister, and I think, a kind of time and space machine.

What sparked your initial interest in film?

As a teenager and a young adult, I was working with photography and poetry a lot but feeling itchy and unsatisfied. I moved to San Francisco in the early nineties, after college. It was this explosive time for confrontational, aggressive art. And because of the AIDS crisis, largely, we turned to this radical expression of queerness. We were coming right on the heels of the early, explosive days of ACT UP and Queer Nation, just at the start of protease inhibitors, drugs which finally made it so AIDS might not be a death sentence. And the dyke community in San Francisco took great inspiration from the activist landscape, turning it into a sex positive, post modern pastiche with tons of heart. All kinds of performances were happening, alongside the activism.

And you pair that with the incredible art house cinema that San Francisco had since the seventies, eighties, and definitely in the nineties. It’s really diminished now. But I went to movies that blew my mind. I didn’t know you could make movies like that. I saw the most random assortment of films in a short span of time. I saw Bertolucci’s The Conformist, a French film called Latcho Drom, Todd Haynes’ Poison. It was also the explosion of New Queer Cinema, a key moment in the 90’s. And I realized that film was a way to put it all together – history, sex, politics, words, images.

At film festivals, there was this growing body of international queer, short experimental work, you know, stuff that you would never just find on TV. This is at the same time that X-Files and Friends were on. Our world was really different!

San Francisco is different now, of course, but I don’t want to be nostalgic and lament a certain period because it is always changing and has to change. We were benefiting from something else being lost – from an entire generation of gay men being lost, in a weird way, because it ignited us. I wouldn’t wish for it, but it generated something, you know. And certainly we were displacing other people, as artists often do.

You have to be willing to let it happen and let it go. Take the energy of the time and hopefully replicate it in some way. Part of what I love about this neighborhood here, Kreuzberg, is

seeing the really old punks. I’m like, dude, that’s hardcore. You’re still living the life, you know. You never see that in LA.

What plans do you have for after this residency?

Forcefully keeping my calendar open! I have had so much time and space here. It’s so rare for me because I have a full-time teaching job and it can be so hard to make any room within that work for creative thought, let alone making new work. So I think the task for me is to figure out how to keep that space open.

I’m shooting another new little film in Berlin in January just before I go back to the U.S.

And I have two other films that I’m finishing that will probably be done by the summer. So I’ll be in LA editing those. I don’t go back to CalArts until next fall, which is amazing.

I have a short residency in Iceland this spring, too. There’s something about the light in northern places that is specific, and to me, fragile. I’m really drawn to it, to photograph it. I noticed how late in the fall people eat outdoors here. Partly I think it’s because Germans smoke a lot. But also, I think it’s the feeling of wanting to drink up all the light possible. I wonder if that human sort of thirst or hunger for light and warmth is related to this thing about how we might relate to natural systems. I’m also interested in places and cities that have rewilded themselves, you know, and have a sort of un-worlding going on, transitional places. So I’m still hunting for more images that go with the human-as-archive film.

I like the idea of relating to natural systems, like we’re no different than trees.

We are different, though, right? We’re not different in that systemic way, but we’re different in our cunning, in our strategy, to have more and go faster. Industrialization definitely plays a role here, something that made us go in this direction. Now it’s really a question of how do we engage critical thinking about natural systems? I’m not suggesting we drop every intervention we’ve ever made in what was natural. That’s flawed logic and easy nostalgia. A lot of queer people have been told what they do is not “natural” and it’s wrong because it’s been proven in nature that there’s lots of homosexual behavior. But it’s that we’re not doing a great job of integrating technology in a way that isn’t a slave to empire. How can we integrate labor with things like the seasons? As an example of a critical engagement about what’s considered natural.

I think that’s where some of this recent science about how other systems live is really helpful. You know, the trees shed their leaves for a reason. What is a human corollary of that for our times?