Meet the On-line Artists // BAKERBREW

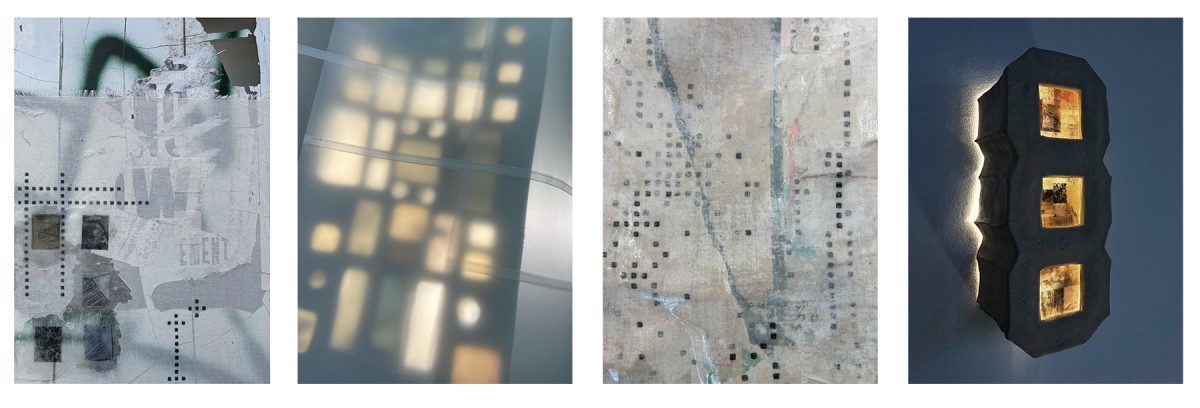

BAKERBREW is a collaborative duo composed of Maddie Baker and Ella Brew, both multimedia artists from the US. Their work resides at the crossroads of sculpture and design. Utilizing materials sourced from nature, technology, and urban environments, they intervene with these systems through acts of imitation, reordering, distortion, and destruction in their studio practice. They aim to disrupt embedded power structures while exploring their aesthetic possibilities as survival forms within the constructed world.

Who are you?

BAKERBREW is a collaborative project between Maddie Baker and Ella Brew, working somewhere between drawing, sculpture, and design. It began at Bennington College in the U.S. in 2022 and is currently continuing in Berlin.

How would you describe your artistic practice?

Our practice is one of place-based observation, collection, and transposition. We are not bound within any medium but are always drawn to materials that translucify, mattify, and/or merge our found material.

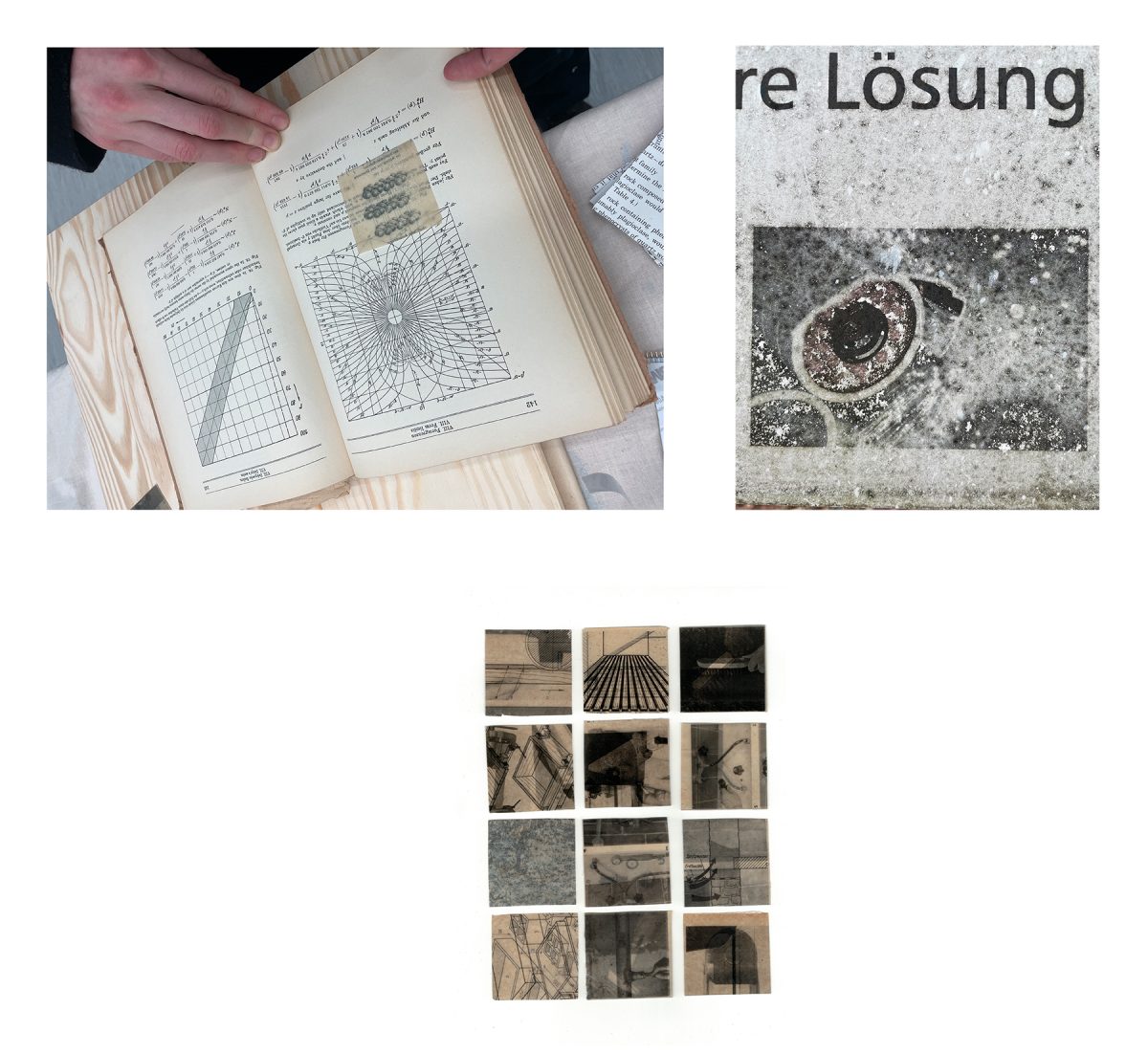

It’s also defined by a shared interest in structural and visual systems around us—discovered through a shared fascination with 80’s and 90’s editions of Electronica magazine—which we found piles of in the basement of a toy museum in CDMX. Our manipulation of its contents into new nonsensical diagrams allowed us to open a visual path between confusion and curiosity. Since then we’ve continued to draw largely from found objects, instructional images, and a collection of discarded printed material.

What is your methodology or process for creating a new project? How is your work as a duo?

One of our most important processes of collection involves walking and noticing together. Forms of functional city elements are discovered and cataloged, and visual material is collected. New ideas for projects emerge from what we notice.

Material exploration remains crucial when manipulating and understanding our sources. Exploring methods of illumination and transparency has been one way of discovering kinetic, living qualities within the work. New intuitive visual languages are uncovered as we layer our hand within found material. An example is using perforated aluminum sheets as a drawing tool: commonly found in urban architecture, stores, and buses, this structure becomes a tool for mark-making—extracting our own patterns from the once-static object and changing its original use.

The continual exchange of ideas defines our collaboration as a conversation—an ongoing dialogue not just among ourselves but also with the material. With two minds guiding our choices, a strangeness emerges in the work that wouldn’t be possible without the influence of the other.

How do you select your material? Why are you drawn to aged or discarded media?

How do you select your material? Why are you drawn to aged or discarded media?

We seek visual elements that go beyond one singular visual world—ones capable of situating each other in a new light. We avoid any source, aesthetic of line or color, or shape too tethered to one connotation. The goal is not to collage but to seamlessly merge into a new surface, so we seek multi-worlded images and shapes.

We continue to seek out discarded and decaying media because we’ve learned that certain colors only emerge in aged form, and that as city structures live and wear, they reveal layers of marks and material. The transparency emerging from disintegration also tells us what was and what is. Being not made from our hands or heads, our found starting material is energized, not passive, and full of memories outside of our own.

What have you decided to focus on in your current project at GlogauAIR?

Our current project focuses on merging three found elements into new artifacts: graphic forms from infrastructure, paper from handwerk manuals, and errant collected marks from the street.

This time has allowed us to finish several illuminated ceramic sculptures based on shapes pulled from sewer grates and bricks. As we continue to settle into living here, this first project was a shifting introduction for us to some of the design and material of Berlin, especially the things beneath our feet.

During this time we’ve also developed a new print practice involving pasting fabric posters in the street. After a few days, the leftovers are stripped from their surface and brought back to the studio. Used as tools for excavating past layers and capturing new ones, these skins seek the unfolding action at public sites as a mark-maker. The result is a sort of hyper-aged drawing—an active participation turned into a landscape painting.

And finally, this time has allowed us to reconsider our cataloging methods, understand the importance of our base materials, and prepare new images for an upcoming book project.