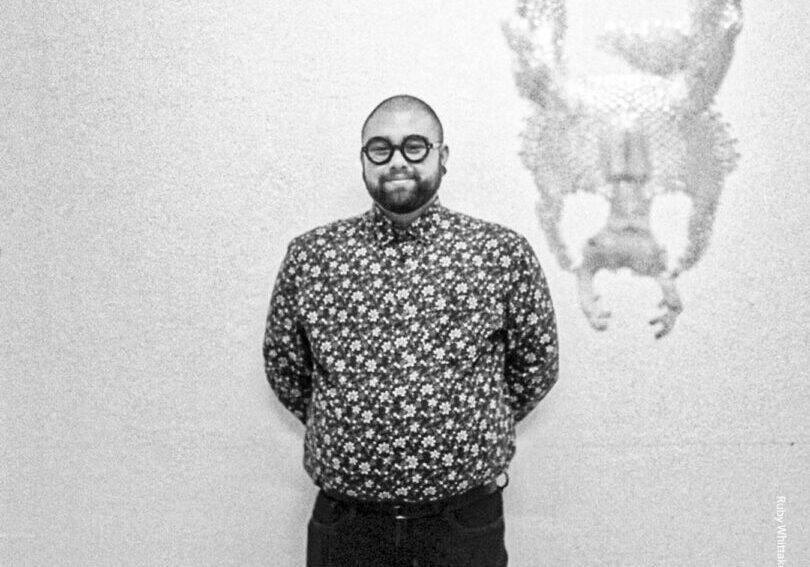

Meet the On-line Artist // Annette Karin Richards

Annette-Karin Richards is a New Zealand artist and writer working across photography, drawn to environmental portraiture, expressionist abstraction, and landscapes. Her practice probes the deep imprints of colonialism, not as distant histories, but as living relationships etched into people and place. She listens to silences, to what has been hidden or erased, working in the thresholds between memory and forgetting, absence and presence, decay and light. Her images emerge from spaces where grief and resilience co-exist, offering not answers, but openings.

How do you use photography to explore the ongoing impact of colonialism in your work?

Photography, for me, is not only about making images — it is about listening to what lingers in the fractures of history. Colonialism severed connections to land, culture, and belonging, and those echoes are still with us.

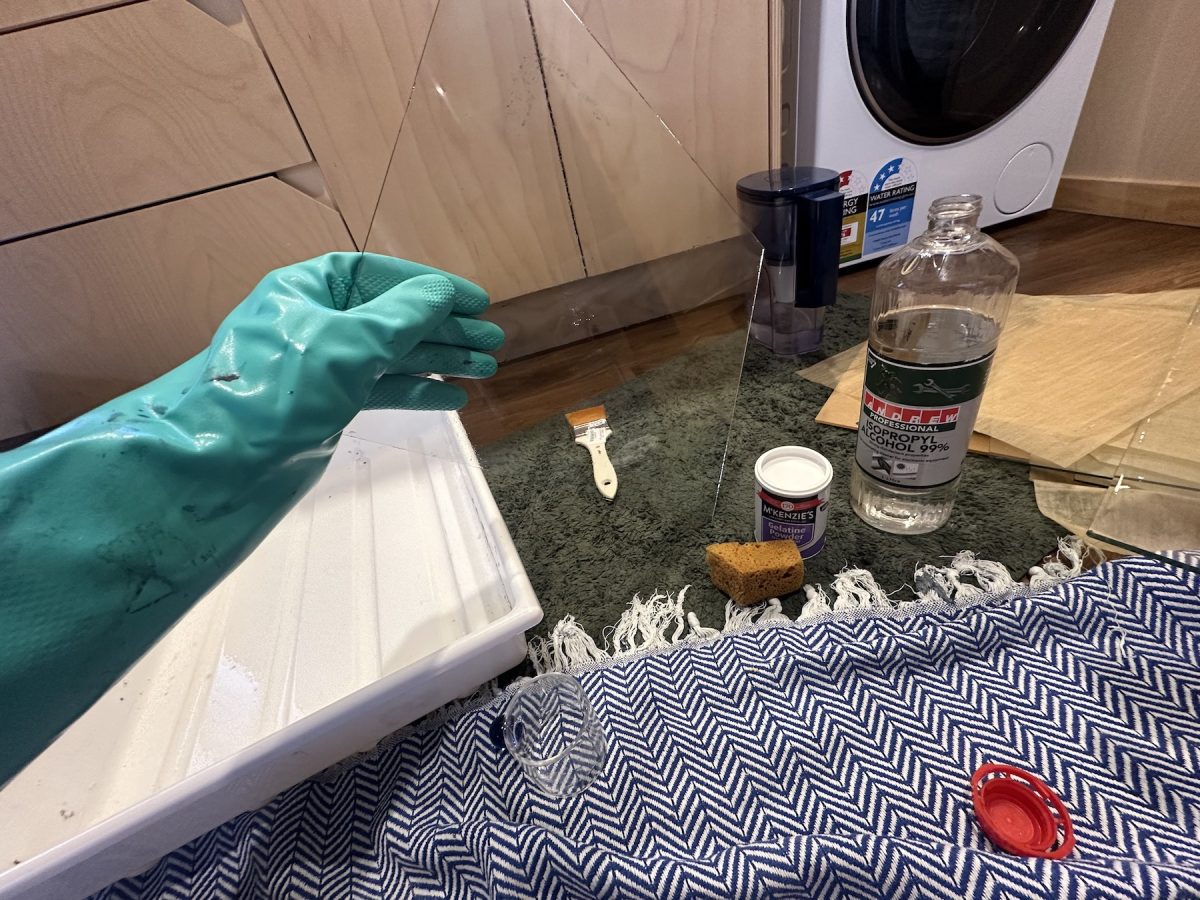

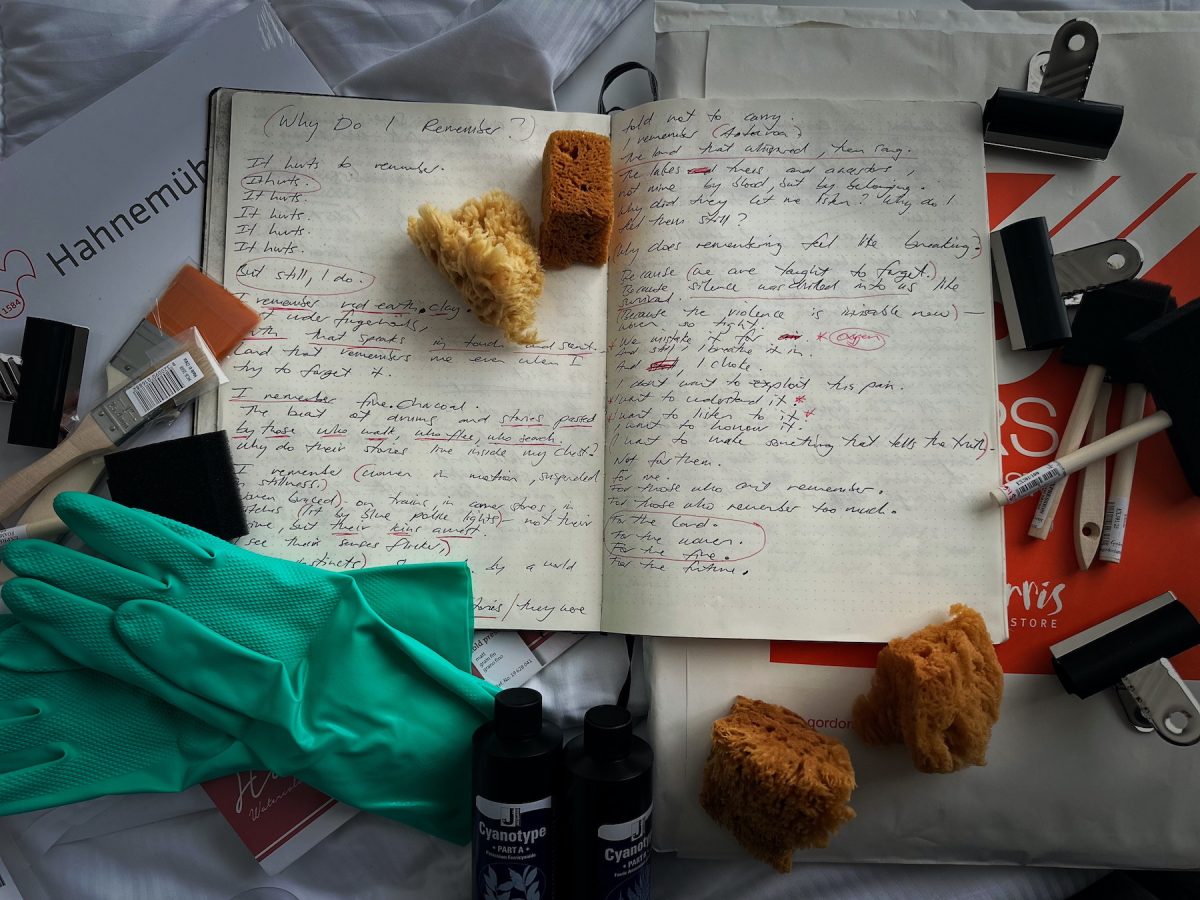

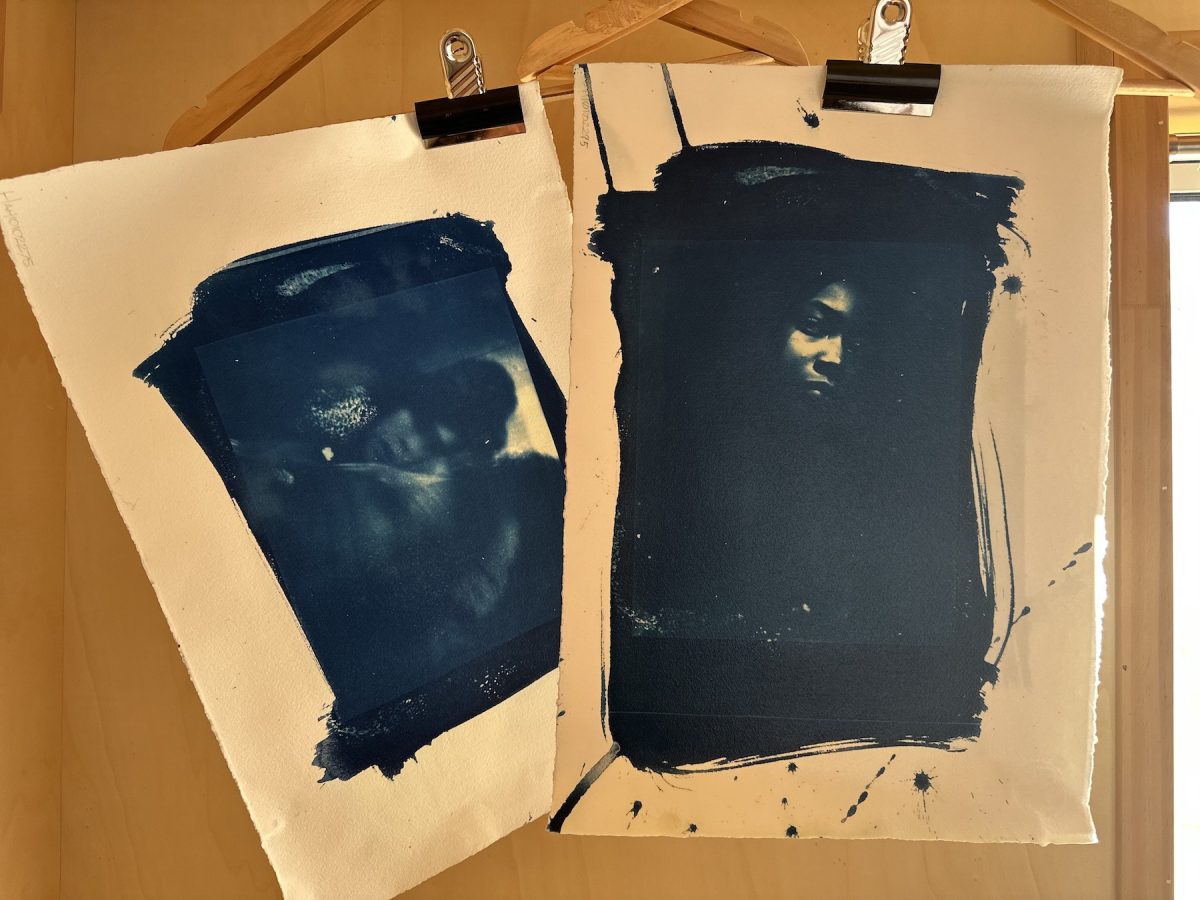

I work with fragile 19th-century glass processes, embracing imperfection, cracks, and accidents as a language of memory. Each plate becomes a site where grief and resilience coexist. The photographs are not fixed objects but living traces of rupture and repair, carrying the weight of what is remembered — and forgotten.

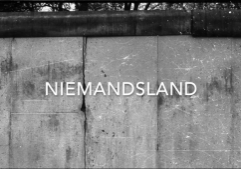

Can you tell us more about your experience in Berlin and how it influenced your current work?

Berlin was pivotal. Especially time in Kreuzberg, Kotti, and Little Istanbul — places where fracture and resilience live side by side. That coexistence has shaped how I think about rupture and repair.

But Berlin was only one part of a wider journey. I had been living in Denmark, studying a master’s in photojournalism focused on crisis and conflict. When I realised that path wasn’t mine, I left, and that decision opened space for art. I travelled through Germany, Belgium, France, Holland, and the UK before returning home to Aotearoa. Each place left its trace, but Berlin’s rawness continues to inform how I photograph memory and belonging.

How does your current residency connect with your broader artistic journey?

This residency feels like a convergence. The darkroom is not only a technical space — it mirrors my inner work. Just as the emulsion clings imperfectly to glass, I’m learning to accept what clings in me and to release what no longer serves.

The journey across continents — my birthplace in Olpe, ancestral sites in the UK, the layered histories of Europe — has deepened my sense of connection to Aotearoa. Returning home, I’ve realised that our belonging here flows through the manaakitanga of Māori, whose generosity allows us to stand on this land. That reflection is now at the heart of my work.

What is the role of abstraction in your photography?

Abstraction lets me move beyond representation into something closer to memory — layered, fragile, shifting. I’m less interested in showing what something looks like than in making visible what it feels like: grief, recognition, resilience, belonging.

The cracks, the uneven coatings, the way light leaks and stains — these are not mistakes but the work itself. They echo how memory moves: fragmented, porous, bleeding across time. Abstraction offers space for viewers to enter the work and locate their own stories within it.

What have you discovered about yourself through this residency?

That the work and the life are inseparable. In the darkroom, fragility is not something to resist but to embrace. The slow process of coating glass, of watching light emerge and dissolve, is also the process of learning how to live — with openness, with release, with attention.

At this point in my journey, I’ve realised the work is not just about photography. It is about purpose, about how to inhabit this life fully — present, rooted, responsive to both light and fracture.

Is there a specific memory or place that has shaped your work during this residency? How did you include it in your practice?

Is there a specific memory or place that has shaped your work during this residency? How did you include it in your practice?

Yes — several, across different timelines. In Olpe, Germany, my body remembered before my mind did — a recognition etched into place. In the UK, ancestral threads surfaced. And here in Aotearoa, my sense of belonging has been reflected back through Māori manaakitanga — a reminder that belonging is granted through generosity as much as through land.

Those moments filter into the darkroom. Each plate becomes a mirror of layered experiences: light breaking through fracture, belonging redefined, memory surfacing. The work has become both art and healing — showing me that the cracks are not endings, but beginnings