Meet the Artist // Jia-Jen Lin

Interview Jia-Jen Lin

GlogauAIR Artist in Residence 2017

- You were born in Taiwan, but are based in the USA for quite some time now. How do you believe that has helped your artistic practice? Is your fascination with hybrid cultures and shifting identities due to this cultural exchange?

I had quite a traditional education in Taiwan, culminating in a Western Painting and Art Education undergraduate degree. After a year as an art teacher in high school, I then attended a master’s degree at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University in Boston. As a result of the school’s liberal and inspiring academic approaches, I discovered a new language of creation, learning how to integrate different media and express my subjects from more critical perspectives.

My works are often related to my personal and life experiences, with particular focus on culture shock and shifting identities. Since moving to New York, I’ve gained a better understanding of the possibilities of an artist’s role and learnt that art can both empower human experience and reflect social phenomena.

- Unlike other artists you don’t necessarily focus on one specific topic at a time, but work on several different ones at once. Why do you feel the need to change what you are working on so often? How do you normally come to choose the subjects of your works?

My works are mainly about process—the process of making, of experiencing, and of becoming. I have several subjects that I have been exploring over the past 12 years, such as human experience, body imagery, cultural differences, artificial nature, and the relationship between manufacturing and art making. Now I usually develop a main concept for at least one or two years.

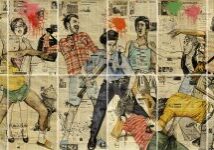

While looking at the art I have produced over a short period of time, it might seem that I work on two or three different topics simultaneously, or frequently switch between them, but they are actually connected and just appear under different titles or in different media. For example, the action of making and questions about society appear in my sculptures in the Manufracture Series but also in the performance collaboration titled Yǐ shǔ yí shù yí shú yí shū yī shù yǐshū yì shù, in which a performer sewed a long roll of fabric while reading a poem querrying our social values and systems.

- How does your artistic process usually work?

Drawing on personal experience, I employ my body and mind as a platform to process the information. I start by research on relative subjects and the materials or objects that I might use. In general, my main stimulation comes from displacement and alienation, our synthetic selves and behaviors, and humanity’s experience. It’s like an ongoing investigation into the relationship between “the self” and “otherness,” rather than the self-obsession some may attribute to artists.

Instead of always working in the same way, I prefer to find new means of presenting and enhancing my ideas. It has always been challenging to transform abstract ideas into visual presentations and written words for the audience to see, read, and re-experience. But I enjoy working through experience, process, struggle, resolve, and sharing.

- You have recently stated that you use “sculpture integrated with photography, video, and performance to portray the ongoing negotiation between our latent desires and the manipulated realities in which we find ourselves”, could you please further explain your statement?

I like to explore the concept of sculpture with a broader range of media. I mostly employ sculptures, photographs of sculptures, video documentation of the process, and performance collaborations and integrate them together into the final presentation. I often try to grasp the glimpse between our everyday norms and our psychological selves beneath this. Because we are living in an environment where most choices and algorithms are preset our ongoing negotiations with society’s systems become inevitable. It then only becomes possible to achieve happiness through feeling we have control in these systems, or through abandoning them and their accompanying social values.

- The inspiration for the project you have been developing during your stay at GlogauAIR – Funes’ Broken Mirror – comes from Jorge Luis Borges’ short story Funes the Memorious – the tale of Ireneo Funes, who, after a bad head injury, acquired the amazing talent—or curse—of remembering absolutely everything. In what way would you connect that to your practice and through what kind of media would you express the connection?

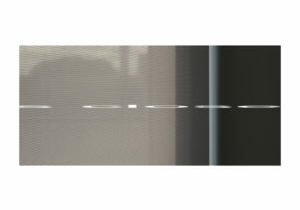

Funes’ Broken Mirror explores the process of searching for and reconfiguring memories. It conveys how we can modify, override, and remap memories into new terms and terrains through a variety of physical and visual experiences.

In this series of modular works, I re-edit sculptures, found objects, videos, photographs, and sound elements that I have collected from different times and spaces. By combining new and old elements, I modify and juxtapose them in a new environment structured with mirror-finished stainless-steel sheets and rods. The reflections of the objects and images resonate with themselves and also with other elements in the space. Through interaction with each other in an isolated space, new associations can be generated.

This project is inspired by Jorge Luis Borges’ Funes the Memorious novella, in which he depicts Funes as a man who remembers everything and thus is incapable of thinking. Everything is forever imprinted in his mind as a vast mirror of the world, and his most distant memories are as vivid as those of a moment before. I began to imagine how the world might look from his perspective and if we can break this vast mirror and recompose the fragments into what we would like to see.

When I was struggling to find a conduit for my abstract idea and the method of creation for this project, I found inspiration from reading The Brain That Changes Itself by Norman Doidge, more specifically the chapter Turning Our Ghosts into Ancestors. This explains how our experiences are linked despite differences in time and space. Memories are actually different every time we recall them, but with consciousness they can gradually be modified and turned into permanent long-term memories, after a certain number of reoccurrences of new events.

I see each object as carrying its own memories, which are actually projections of our personal histories. Therefore, we create associations between objects and the meanings of objects that reflect our own memories, which also change from time to time. Although here I am using my personal process of memories to experiment with this idea, I have had feedback from people whose experiences mirror my descriptions. I think this is the most important aspect I would like to provide those viewing my art—to share common but likely forgotten human experiences.

Resulting from my residency at the International Studio & Curatorial Program (ISCP), New York, and continued exploration at GlogauAIR and gr_und, Berlin, “Funes’ Broken Mirror” will be presented at the Rubber Factory in New York in April 2018.

- In your recent works like The Manufacture series and The Factory Series you have been exploring the relationship between manufacturing and art-making. One can’t help but notice the connection to movements such as Dadaism and Pop Art where the use of manufactured goods was a common practice in order to convey a certain idea. Could you explain how your approach differs from that of artists from that era? What exactly provoked your interest in bringing these two, quite often conflicting, practices together?

My work is not really related to Pop Art, but people might associate some of my work with Dadaism since I often use found objects and sometimes create performance collaborations with different elements, such as visual art, performance, poems, and sound art. When I started to employ a lot of found objects in my work from 2010, I looked at some visual results of Dadaists’ activities, their creation processes, the way they decoded the meaning of objects, and their randomness as well as improvisation, so, yes, there is some influence from Dadaism in my sculptures and installations. However, I don’t see my idea of creation as really aligned with Dada’s main concept—anti-art activities from social and political perspectives (although, of course, Dadaism is more sophisticated than this loose definition suggests).

Instead, I have been inspired by works from Arte Povera artists, with their emphasis on life as art and the return to simple objects and messages, and the Fluxus, which is more focused on attitude (rather than style, or a movement like Dadaism) and often intersects with different media.

- How do you believe your stay here at GlogauAIR and Berlin has influenced your work?

My stay at GlogauAIR provided me with time and space to continue my projects. I was able to experiment with video installation at the studio and later present the results at gr_und. Being in Berlin also gave me a brief insight into the art spaces, underground music scene, and artists’ communities of Germany’s capital.