Meet the Artist // Arta Delharte

Arta’s body of work encompasses an undisciplined, appropriationist, and Conceptual practice. Arta seeks to explore the intersection between the pictorial and the digital. Addressing themes such as the transcendence of pictorial connotative codes, the Internet, and the problematic pictorial references we have inherited in the category of “geniuses”. Through different media, Arta seeks to free the spectator and invites them to reflect, whilst emphasising that everything concerning her practice originates from the pictorial.

Can you tell us a bit about your background and the project you’re working on during this three-month residency at GlogauAIR?

My practice begins with painting, but from the very start it’s been driven by an interest in how images circulate, how they’re produced, and how they become distorted. Living in the time I live in — and carrying the weight of everything that’s historically been defined as “art” — I can’t help but try to create something that speaks to the present, without forgetting everything that came before. For me, all of my work is archive, because it’s rooted in historical material. And it’s all pictorial, because it all starts with painting.

That research inevitably led me to question what images really are, how we consume them, and what effects they have on us. My last exhibition, FAKETORIES, dealt with all of this in relation to cultural spaces, the factory, the history of images — and more specifically, the first moving images by the Lumière brothers. In the video I made in collaboration with Dolorcica, we revisited texts by Hito Steyerl and Harun Farocki, asking ourselves where the exit might be from this regime of image-consumption we live under — where we’re slaves to the screen, and the only thing we’re offered is the chance to consume ourselves.

Eventually, I understood that this “exit” doesn’t exist yet — and I’m not even sure it ever will. So I proposed something else: to open a window and install a slide. It’s not an escape, but it’s an alternative. And honestly, beyond all the layers of theory, I just wanted to create something that wouldn’t add more suffering to this 2025. A fun, absurd little moment for the people who came to the open studio. Of course, you can find meaning in the act of sliding down, the speed, the impact… but right now, I’m more interested in something lighter, more mundane. There’s space for that too.

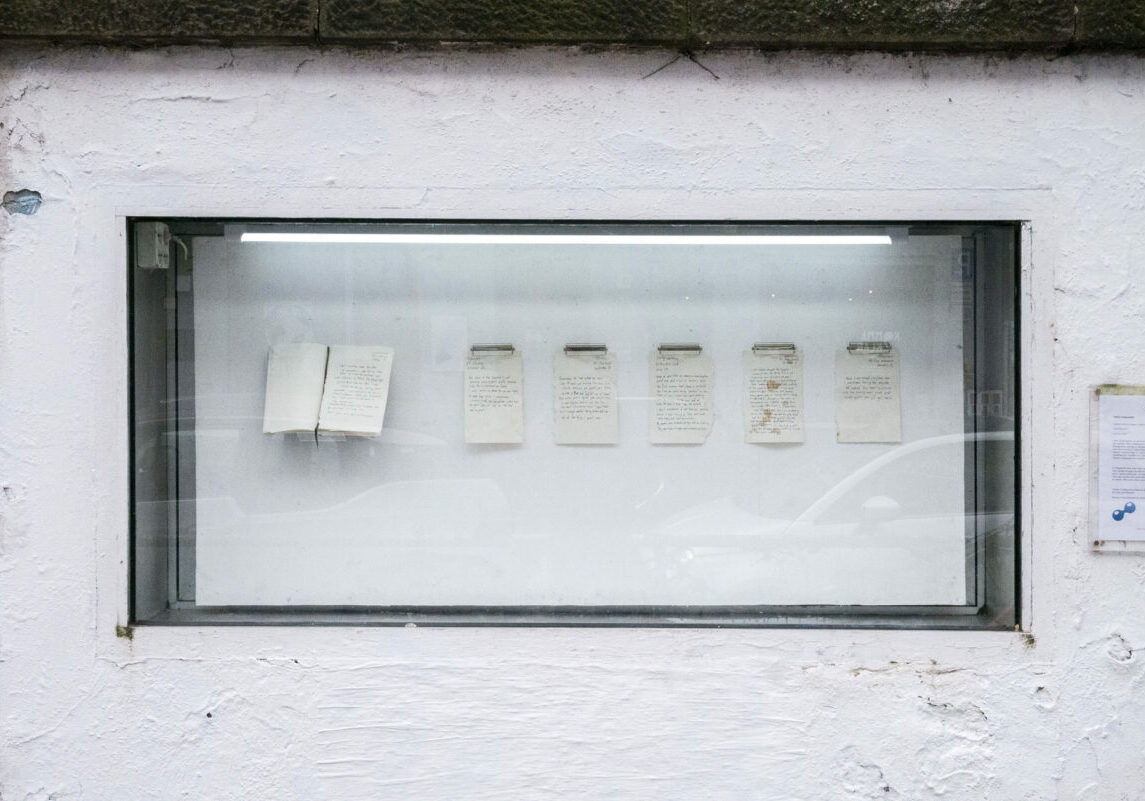

At the moment, I’m working around the concept of the slide—not necessarily as a functional object, since I currently lack the means to produce a usable one, but rather as a conceptual entry point into a project that is deliberately open-ended. The slide becomes a placeholder, a speculative interface for thinking through trajectories, descents, and failures of structure. As such, what you’ll encounter in the open studio might be anything—or nothing at all.

So, you said that your work starts with painting but also connects with the digital and the conceptual. So how is this mix reflected in this new project for GlogauAIR?

When I say my work starts with painting, I mean it in a deeper, almost primal sense. For me, painting was the first innate symptom of being human — the impulse to express, to communicate, to create something. I think of Altamira, of those first marks on stone. Sadly, that symptom has ended up confined under the label of “art,” but I see it more as the act of creating images as a form of language.

I don’t really believe there’s a strict separation between the pictorial, the digital, and the conceptual. It’s not about connecting them — they’re all part of the same continuous story. One is the development of the other. Virtual images are not separate from painted ones; they are their evolution. Also I believe that, intentional or not, all contemporary art is conceptual in its structure

Honestly, I don’t know if all of this is reflected in the project I’m working on right now — and I’m not particularly worried about it either. I’m more interested in inhabiting the question than trying to answer it.

You have mentioned before, Hito Steyerl, Altamira Caves. What artists, works, or texts have been fundamental in the development of your past works, and how do they relate to the project you’re working on now at GlogauAIR?

As I had already mentioned, artists like Hito Steyerl, Harun Farocki, and Walid Raad have been essential in helping me think of the archive as a fictional and political construction. From Steyerl, The Wretched of the Screen and her video How Not to Be Seen have been particularly influential. They’ve helped me understand how invisibility, fragmentation, and oversaturation function as strategies within the contemporary image ecosystem. Steyerl doesn’t just critique the dominant visual regime — she also proposes tactics to resist it through artistic practice.

In Harun Farocki’s case, his book Distrust of Images was a revelation. It taught me to be skeptical not just of what images show, but of the structures and mechanisms that produce and circulate them. That critical stance deeply influences how I work with found footage, screenshots, archival material, and optical devices. Both artists have pushed me to rethink the systems of image connectivity and consumption we’re embedded in, and to better understand the current state of art and visual culture in this post-human, algorithmic era — a time when images operate not only for human viewers but also between machines, independent of us.

Equally fundamental to my practice are the writings of Paul Virilio and Jacques Derrida. From Virilio, I draw on the idea of speed as a form of power and violence. From Derrida, the concept of the archive as something always incomplete, contested, and unstable. These ideas permeate my work and are at the core of the project I’m developing at GlogauAIR: a visual investigation that seeks to open cracks in the polished surface of contemporary imagery — proposing zones of interference, suspicion, and fiction.

You describe your practice as undisciplined and appropriationist. Can you expand on these characteristics, on how these characteristics manifest in your work and what you aim to transform through them?

I use the word “undisciplined” ironically. In my context, when someone calls you undisciplined, it’s in a very pejorative way — “what an undisciplined little girl!”— and I found it funny to reclaim that term instead of saying I’m multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, or transdisciplinary — terms I find very confusing for a non-specialized audience to understand.

It’s true, I don’t have an exact discipline, and I don’t want one. I’m not looking for a discipline. For me, “Undisciplined” feels messier, freer, harder to categorize — and that suits my practice better.

Appropriation appears in my work both as a method and as an attitude: I rewrite images, quote without permission, turn found fragments into part of a personal narrative. It’s not just about using what already exists — it’s about intervening in the way images circulate, hacking the authority of the original. Often, there’s no need to add much more, because, as I already said, everything has already been done. What changes is how we look at it, how we shift it, how we make it speak differently.