Meet the On-line Artist // MARIO DAVALOS

MARIO’s work approaches water as psychic matter, following Bachelard’s idea of the element as imagination, memory, and inner life. He engages landscape painting as a historical tradition, while shifting its focus toward the simulation of nature as a contemporary substitute for nature itself. These paintings do not describe the wild, but its domination: environments engineered, contained, and aestheticized. By painting constructed landscapes, MARIO questions how control, comfort, and progress have replaced intimacy with the elemental, revealing the quiet violence embedded in our images of paradise.

Can you give us a brief introduction of yourself? Specifically, we would love to hear about your background

I’m a Dominican artist working primarily in painting, with a parallel career as a strategist and founder of a communications consultancy.

After two decades building creative enterprises, I’ve returned to my artistic practice as the center of my life, integrating everything I’ve learned through travel, research, studies, and professional experience. Alongside painting, I’m also a photographer and writer, and I’ve led expeditions to remote natural environments—such as the Arctic tundra, Antarctica, and the Amazon—which have become central to my thinking and visual work.

My interests extend into philosophy, ecology, and the ways contemporary society constructs meaning around nature, progress, and abundance.

How would you describe your artistic practice?

I am a painter before anything else. The way I see the world is through the eye of a painter, moving between figuration and abstraction. I work mainly with oil and mixed media on canvas, producing medium- to large-scale works that often function as part of larger bodies or series rather than as isolated pieces.

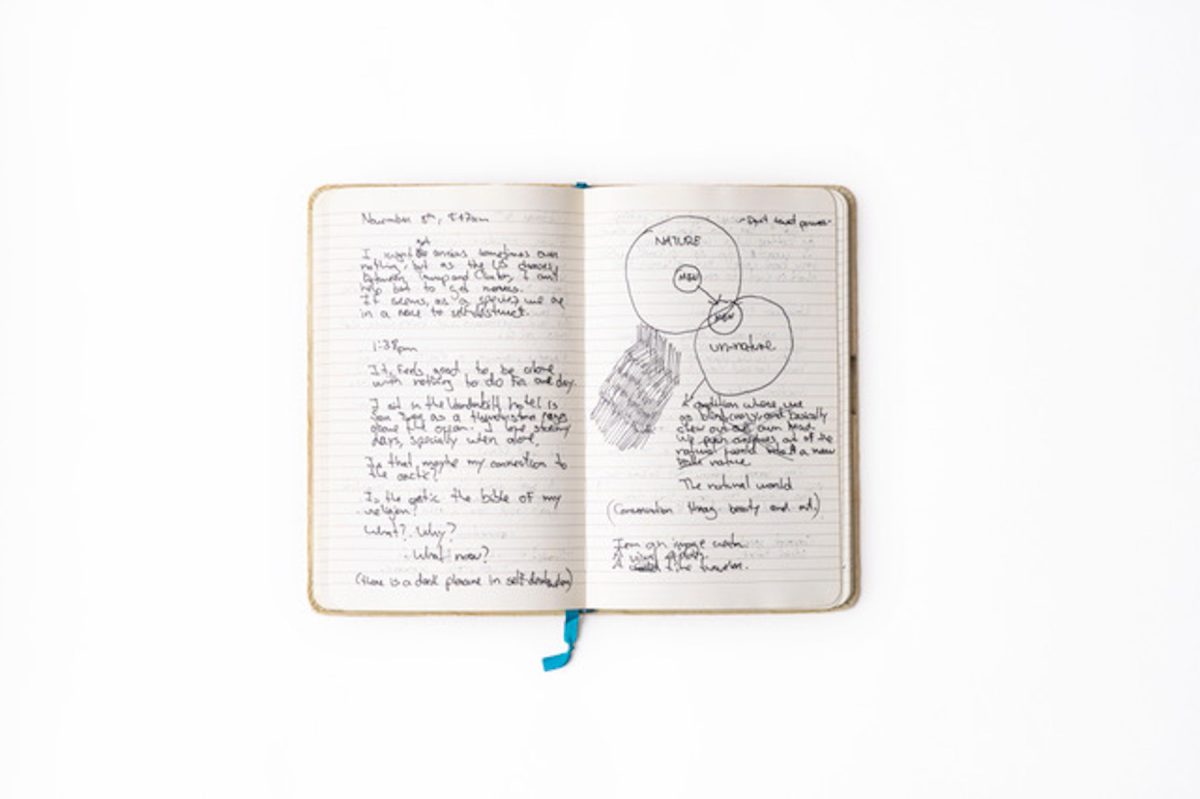

Conceptually, my work explores the contemporary relationship between humans and nature—particularly how nature has shifted from being a lived, spiritual, and existential space to becoming a resource, a product, or a simulation. Water and land are recurring elements in my work, not only as physical matter but as psychological and symbolic territories.

I’m interested in ideas such as abundance as performance in the contemporary world, the replacement of natural abundance with material or technological abundance, and the tension between wilderness and civilization. I am particularly interested in simulations of nature—pools, gardens, resorts, and controlled landscapes. The paintings often suggest ritual, transformation, or rupture, and they invite slow reading through the subtleties of paint, rather than immediate consumption.

What is your methodology or process for creating a new project?

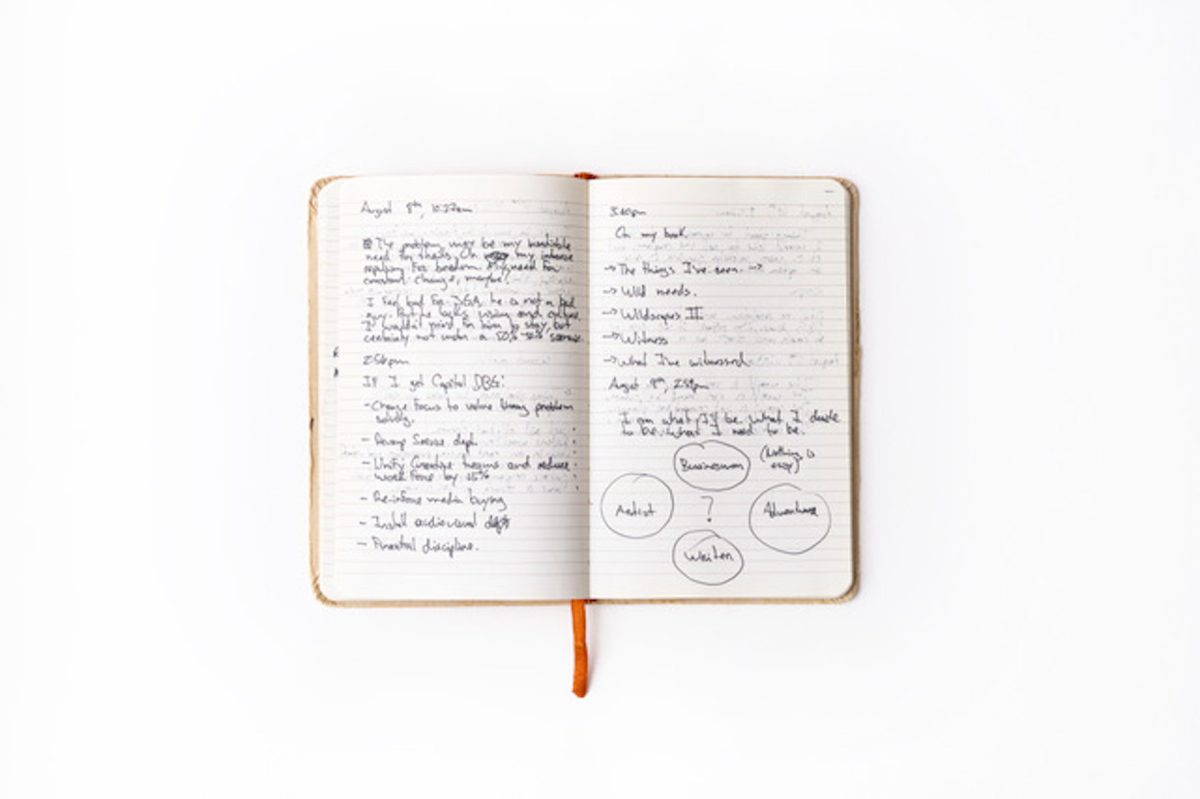

My process begins long before the act of painting. It usually starts with lived experience—travel, immersion in specific landscapes, or extended observation—combined with reading and writing. I keep notebooks where philosophical ideas, sketches, and personal reflections coexist without hierarchy.

From there, I define a conceptual frame rather than a fixed outcome. I’m interested in building a system of questions that can generate multiple works. In the studio, I work intuitively but within that conceptual boundary, allowing accidents, repetition, and the erosion of images to play an active role.

I often work in series, developing several paintings simultaneously and letting them inform one another. Writing is an important tool throughout the process, not as explanation but as a way to clarify thought. A project usually takes months or years to fully resolve, evolving through cycles of production, reflection, and revision. Doubt and questioning are at the center of my work.

What’s the project you’re working on during GlogauAIR’s residency?

During the residency, I’m developing a body of paintings that continues my exploration of water as both a natural force and a cultural construction. The project, titled Forgotten Spirits (working title), focuses on spiritual connections with the land, drawing from research into ancient tribes, folk stories, and the ways in which modern science has gradually eliminated the possibility of mystery.

Visually, the work moves between landscapes that feel almost primordial and scenes that reference artificial or simulated environments. The paintings are not descriptive but experiential, aiming to evoke a sense of dislocation between what is natural, what is manufactured, and what is remembered or imagined.

GlogauAIR offers an important context for this project, providing a sounding board I’ve eagerly missed since art school, as well as a space to slow down production, test new formal decisions, and reflect on how these themes resonate beyond my own geographic and cultural origin.