Meet the On-line Artist // Leanne Finnegan

Leanne Finnegan is an Irish visual artist based in Berlin, working primarily with video and text. Her practice explores the sacred in post-modernity, recontextualizing images to create playful dialogues that counteract alienation and disconnection. She reflects on the “pain of becoming a subject” and the desire to dissolve beyond individuality, drawing on Poetic Imagery, the Religious Imaginary, and Eroticism to seek solace from solitude.

Can you give us an introduction about yourself and tell us about your background?

My name is Leanne Finnegan and I’m an Irish artist. I am currently based in Dundalk but will be making the move over to Berlin in the next month. In 2022, I graduated from my Art bachelors and since then I have been continuing to develop and expand my practice.

How would you describe your artistic practice?

I would consider myself to be a video artist but my practice is quite multi-disciplinary. The work’s foundations are often in research and personal writings which spiral into a video format, or sometimes photography or sometimes objects.

Since I’ve begun working I have always been interested in ideas of spirituality and transcendentalism. At the moment I’m really interested in looking at this in a contemporary context, where the sacred exists today, what shape it takes. I’m also interested in its cultural and personal functions.

Still from Field Trip.

Still from Field Trip.

What is your methodology or process for creating a new project?

I feel like I’m chasing ideas, or answers to my own questions. So the initial stage is a personal reaction and process. Oftentimes I start with a question, or an interest and explore it from a few different angles, trying to find resolutions or remedies. This usually leads me into the realm of esoteric or religious ideas and then that is usually refracted by psychological or more straight laced philosophy – then it comes back to a personal realm of trying to make sense of all the information.

With the next part I like to go again into a more imaginative playful space and build up narratives which react to the ideas, working perpendicularly from each other. This output usually looks like a narrative for a video work. But I also really enjoy making ‘artefacts’ in my practice. Like objects that would exist in that world. I feel like this usually comes from an itch to use my hands again if I have been thinking and writing for too long.

Tell us about the project you are working during your online residency at GlogauAIR.

I have went into this residency with GlogauAIR to develop a film work which is following on from a period of writing and reading. For this narrative I have been jumping between Julia Kristeva’s notions of psychosexual development, Georges Batailles writings on Transgressions, the relationship of physicality and immateriality – particularly outlined by some of the writings of the Beguines movement.

Fundamentally I have been zoning into the idea of burying and dirt as a substance and a character’s act of embodying something higher. It’s been a very enjoyable time fleshing this work out.

My output for this residency which you can see on my Virtual Studios is a series of photographs of spiritual sites – a burial site and a rag bush. This has been a process for me to consider set building for the film. I have been really inspired by the theatricality of the sets of Sergei Parajanov and also Derek Jarman.

Marker #1.

Marker #1.

What led you to explore a multidisciplinary artistic practice?

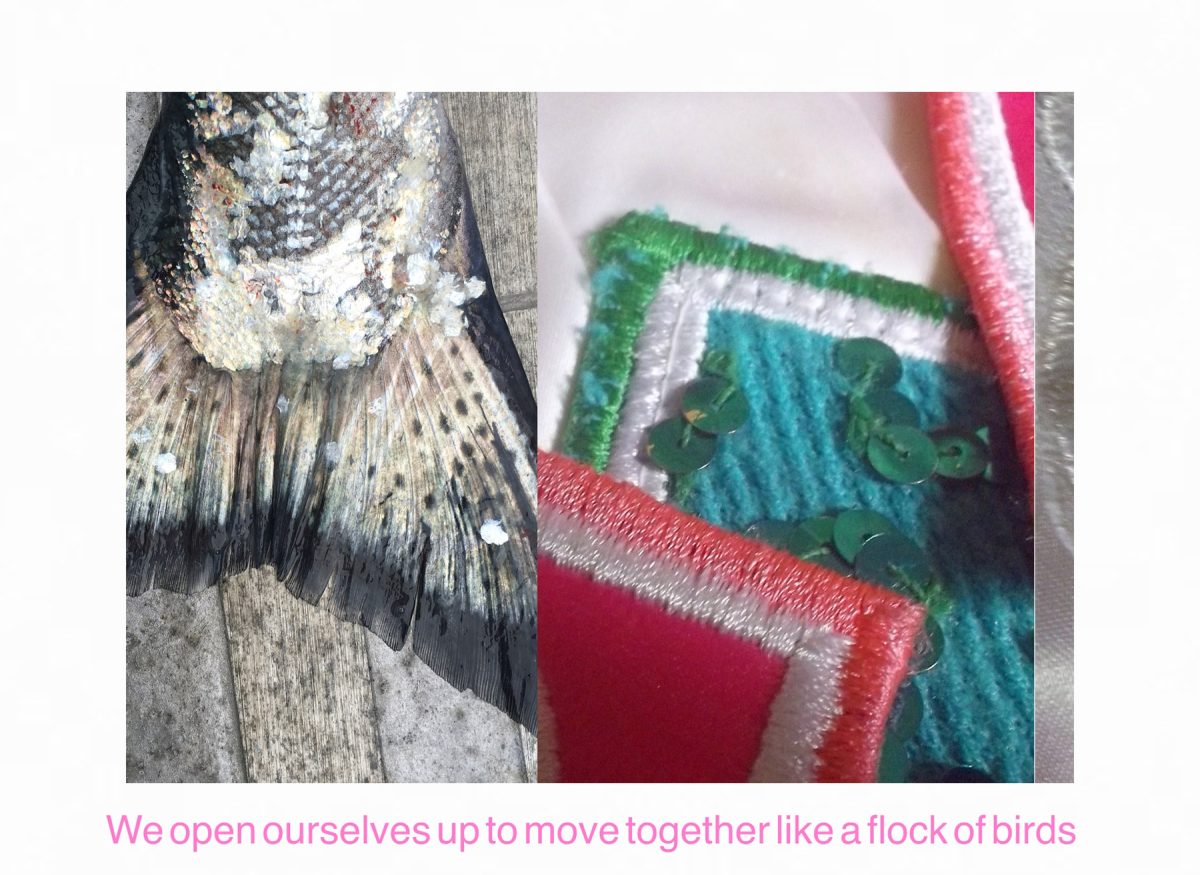

In my work I’m very interested in world building so I like to make objects/images/videos as different expressions and representations for the world in question. Like in this project for GlogauAir being able to make sculptures and textile outputs create a new extension of that world.

And even the act of photographing the sculptures is an exciting process for me because it takes it further into a new context. For me these pictures give an impression that they are documentations of a real site and it’s kind of a work of documentary-fiction.

That’s an example of where I find a multidisciplinary approach to be really satisfying. And as I said earlier, sometimes I just want to make things with my hands.

How do your Irish roots influence your vision and creative approach?

I would say it definitely has, as it would for anybody who has been raised in a culture or space. I can definitely locate the religious interest quite specifically. Ireland, in our recent history, has been an extremely catholic country, which has been deeply embedded into the state. Over the years this has changed and the church has lost its hold on the government and society, but the remnants of it are everywhere and especially institutionally.

When I was younger, I went to catholic schools and clubs and camps, not specifically by the wishes of my family but because the majority of schools and outlets were – so the religious imagination was a part of daily life. There were long periods of masses and sitting in church which burns images, stories and atmospheres into your brain.

Specifically the contrast between the world of the church and the world I knew outside of the church, which in a way felt quite plastic. And not even specifically the aesthetics but also the feeling or promise of a God. I think this contrast has had a large influence.

What were the first moments or experiences that sparked your interest in themes such as the “sacred” in postmodernity?

Like I mentioned above, the early religious exposure has been a major spark for that. But I think I came around to it again in my practice as an older, non-religious person as a tool for meaning-making and as an act of catharsis. I had become really interested in ideas of ‘spiritual poverty’ and probably to a degree existentialism.

I was also very curious about – again back to Ireland – where the place of religion and faith was relocated to in a society which (from my perspective) is no longer as concerned with faith. After decades behind us of really routinely having an outlet for the sublime and ‘higher experiences’, I wanted to see where this energy had been transferred to and what it has transmuted to be.

Still from Rattleback Musings.

Your creative process begins with research. How do you decide which thematic pathways to follow or which ideas to develop?

My process of research has always been by the impulse of private and personal feelings, trying to work them out by reading, which leads to a million different rabbit holes and perspectives.

Again, I like this to happen instinctively. I find for example cross researching to be a very exciting way to work. So I will read for a period of time and think about certain concepts, while also going through archive material, finding images and texts that for some reason resonate.

Then coming to a certain point, piling them all together, and beginning to find links between images and ideas. I find at this point, I begin to get a thicker understanding of how I feel about the themes and the world they live in.

What role does writing play in the transition from research to the materialization of your works?

Writing feels like shaking the cobwebs, it’s a very direct and immediate medium which requires no resources to do and there are no limitations. Writing enables me to put my specific voice and perspectives back into the work.

It begins to abstract and walk further away from the research and the work can take on a life of its own. Which I always find exciting and surprising.

You mention figures like Julia Kristeva, Georges Bataille, and Simone Weil as influences. Which of their ideas resonate most deeply with your work?

I have been really keen to play off two ideas in my new body of work. First is Julia Kristevas take on psychosexual development which is the process that happens from the birth of a baby to around the age of four. When a baby is born, coming from the womb, they see no distinction from themselves and their mother and to the objects and landscapes that surround them, they’re all one in a sense. Pain is shared and everything is an extension of themselves.

Over the course of development, particularly with the introduction of language they begin to – and are taught to – see and seek separations. So through this process they end up as a self-perceived individual with an isolated identity. In my past works, I have been really interested in the feeling of wanting to almost, metaphorically go back to a ‘womb’ state, and dissolute a sense of self. For a long time in my practice I have been thinking about the Womb/Void dichotomy, and how these ideas are viewed differently depending on what culture and time you’re looking at. Notably I was very interested in the contradicting opinions of it. Where 20th-century western philosophers see the void as a place of nothingness and fear, 13th-Century mystics viewed it as a space of endless creation. So still in my practice I’m thinking and working through these ideas.

The second idea, in this specific body of work, is Georges Batailes notion of Transgression. He has this idea that areas in society which are considered taboo (dirt/sex/death) are areas – when faced – can be transformative. As they bring you to an area where you are faced with the limits of your individuality, and where boundaries between yourself, the other and the landscape can begin to dissolve. It offers a disruption in the separations in which we exist everyday. He argues that the act of transgression can offer moments of ‘continuity’ which can be described as a feeling of being in touch with the infinite or divine or as I bring it back to the symbolic ‘womb state’/’return’. So from this I have been thinking about developing this symbol of dirt and digging.

You speak of “antidotes” to alienation in your work. Do you believe art has a therapeutic or transformative power?

I think it is for sure cathartic and a good piece of music, art or film can get you in touch with that sense of ‘continuity’ or sublime.

In your practice, you integrate religious imagination and semiology. How do you think these elements can connect with contemporary audiences?

Kind of like I said above, I’m interested in all images and creations – functional or recreational – as some kind of cry for connection that elicits meaning making. For me putting contemporary materials or language in a format that is inspired by ritual practice can put a light on how those acts and feelings are still very much alive in the collective imagination.