Meet the Artist // Judith Fang

Judith Fang is an independent artist and amateur astronomer whose work explores the nostalgia and disconnection of urban life amidst constant change. Inspired by the night sky as a stable backdrop to her rootless surroundings, she reflects on shared human experiences across diverse backgrounds. Through her art, she connects science, nature, and language to evoke empathy and poetry.

Can you give us an introduction about yourself and your background?

I’m Judith. I graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. I spent four years there, but it was abruptly stopped by the pandemic in 2020. I moved to London for another year of study in the middle of my undergraduate, and afterwards, I moved to a very small town in China.

It’s a historical town of porcelain industry and ceramics. A lot of people who graduated from art school, they’ve all moved to that town. I don’t know why.

It’s probably that they’re like me – there’s sort of a pressure in China in general – because I was born and raised in Shanghai – living in big cities. Everything needs to be done within a social pace that your parents expect, stuff like that. So escaping from urban life to smaller towns has become a popular move in recent years. That also happens in my artwork as well – the theme of escaping from urban life.

I remember you saying that moving there made you realize how many stars there are. Is that when your interest in astronomy started?

Yes, exactly. Because I think the stars really mark how close you are to nature. Every time I was in Shanghai, I didn’t realize that we have so many stars, especially the moon. You can only see the brightest ones in the sky, because of the severe air pollution and the light pollution. You’re living in a bubble of a man-made world. And you don’t really get any idea of how other kinds of life live.

Was that in addition to the work you were doing before you moved to the suburbs? Or did it break away from the work you were doing before?

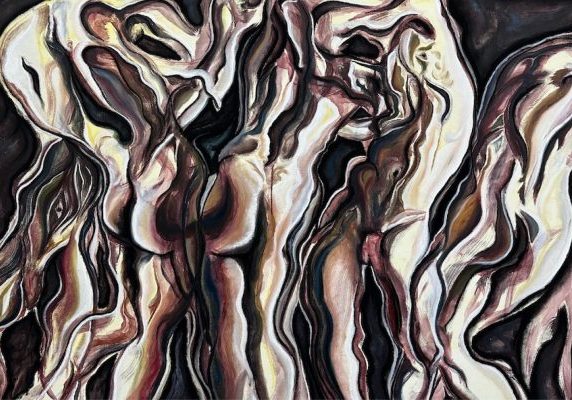

I think there are certain connections. I still have a very long-term anxiety that was from Shanghai, a traumatic experience from Chinese education and pressure from school.

But I drive my art direction a little bit different from before. I was talking about control and being in control at the very beginning of my career. That’s also why my previous portfolio website is called Judith Square. the idea of the square, compared to the studio, is a very open space outdoors. So I didn’t name my studio a studio. I called it a square. And I make every work interact with physics. I try to leave many decisions to nature itself.

For example, I do ceramics. And there are a lot of decisions of the color – the appearance is made by the kiln, by the temperature. I used to work with gravity as well. There are ideas around thinking that I don’t have absolute authority when I’m making art. This is also a sort of anxiety treatment as well.

To me, astronomy perfectly follows that formula. It’s not up to us what happens in the sky or the way the earth turns. Or if a comet decides to come down and wipe us all out. We’re not in control at all. Like in China, during the pandemic, Shanghai was totally locked down at the beginning of the year. And at the end of the year, the little town that I lived in was locked down too. All the shops were closing and people didn’t have enough food. People were drawing in the anxiety. So I just ran all the way to the top of the building, to the rooftop. I grabbed a seat and just sat there stargazing. I realized that the stars rise every single year at the same time. They have their own pace and nothing influences their pace. This sort of macroscopic way of thinking really relaxed me a lot.

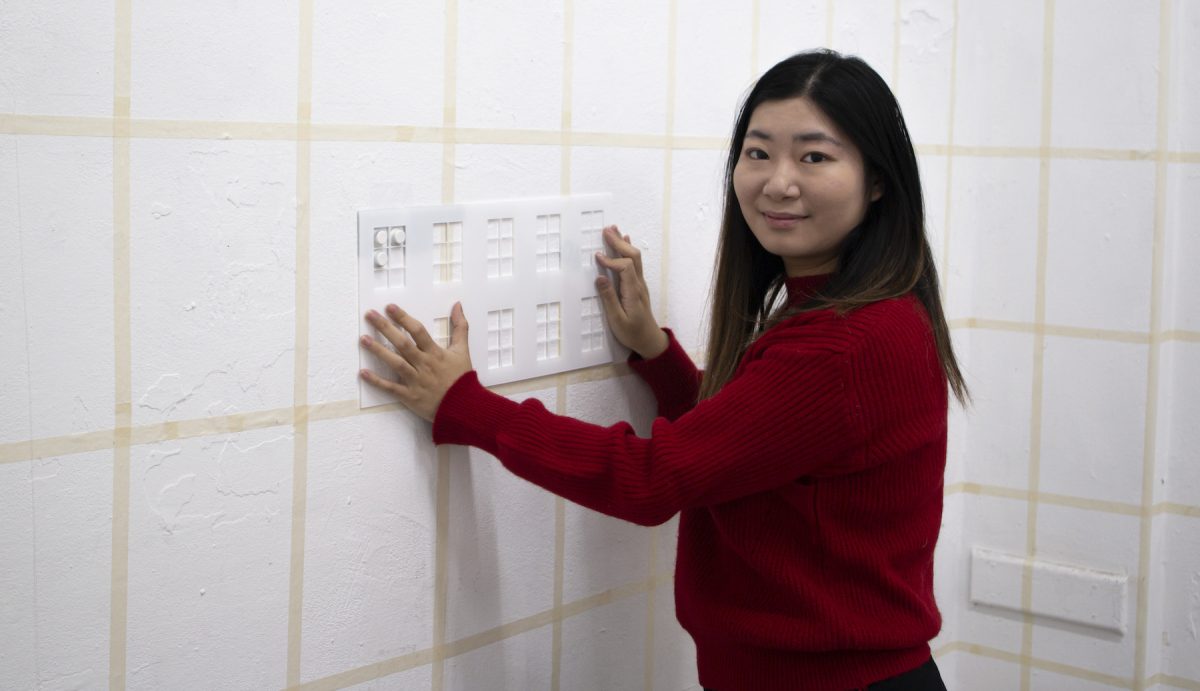

When did the work with Braille begin? Is this recent, and what led you to that?

When I was looking at the stars, there’s a method when you look at them called Star Bridge. You just build compositions between dots to a shape. And then that links by maybe six or five degrees to another star. This is how you seek deeper, celestial bodies, such as galaxies and all the clusters. So I look at all these spots and think about their compositions, trying to link them from one to the other.

This sort of way of reading the stars made me think of them as a language. We’re making sense of it, at least making them into something comprehensible. So when I read Braille, I realised that they have many connections between them. Braille is also called ‘night language’.

There are so many poetic parallels between Braille and stars. Another thing I realized is that when I take my telescope, everything that shows in my lens is reversed from the natural world. So you see everything upside down. This is how you write and read Braille – you write it from right to left and read from left to right. I’m highly interested in the connections between these two semiotics.

As far as being in Berlin, now that you’re almost finished, how has it been working here with your practice as a whole, but also with your interest in Braille?

In my first proposal to GlogauAIR, I wrote that I was going to paint the night sky outdoors. Then I realized it was too cold, so I didn’t do that. I think that Berlin is very inspiring to me in a lot of ways, even the way of living.

The way I’m thinking about graffiti was just a random decision I made. I wanted to try something different because I didn’t want to repeat myself. Eventually, I’m recreating the Braille project with an advanced version. Just to make sure the work affects the audience. But still, I do think that the study of graffiti made me learn a lot about the composition of urban life again. This sort of urban life is not the specific urban life that I was trying to escape. It’s about freedom of speech in urban life. It’s more about how we treat all these languages and voices. Anonymous voices especially.

On the architectural surface, and the urban surface in general. And they have very weird or interesting compositions happening at the same time. With the tracing of graffiti, I don’t know how that would be linked to an independent project yet. The whole idea of graffiti ensured and reinforced my ideas and my interest in semiotic studies. The very blurred boundary between image and text.

What are your plans for after the residency?

I like Berlin, first of all. This is my first time here – I lived in London and I moved to Ireland as well, but I’ve never been to other parts of Europe. I want to come back if there is a chance. I’m still looking for opportunities in Amsterdam. I do want to move out of my original country and I’m trying to seek a new way of living. This is what all my artworks are doing as well.