Meet the Artist // Alejandra Prieto

Alejandra Prieto is a Chilean artist whose practice explores the connections between chemical elements found in minerals and the human body. Through this lens, she investigates how materials extracted from the earth such as lithium, used both in electronics and mental health treatment, can shape our biology, perceptions, and global systems.

Could you tell me a bit about your background and the project you are proposing for this three-month residency here at the GlogauAIR?

In my usual practice, I work mainly with sculpture, often using heavy or even toxic materials like copper or lithium. So I tend to work outside the city, in the countryside, where I also have the space I need. At the same time, I’ve always enjoyed painting with watercolors. I have a neurological condition called Essential Tremor, which makes my hands shake and this complicates the painting process a bit, but that’s exactly what draws me to it. It fascinates me to explore this relationship between my body, its movement, and the paint itself.

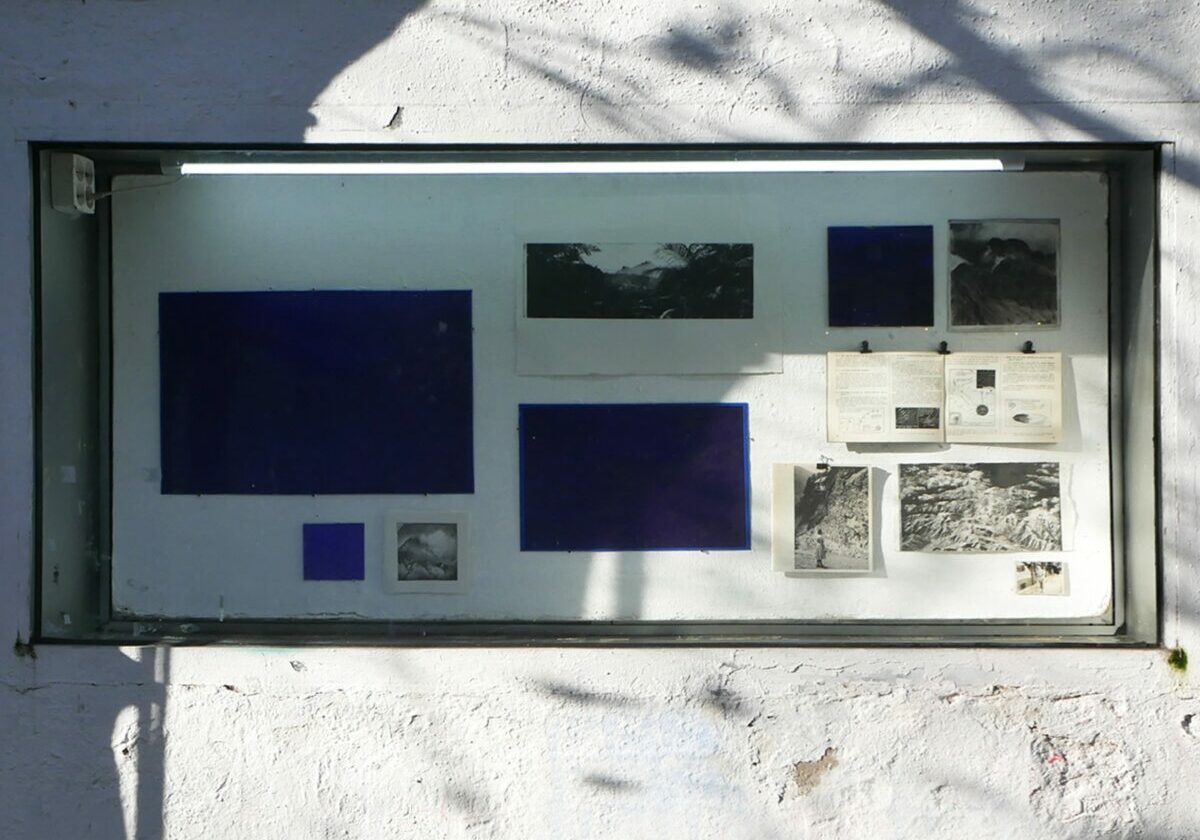

During this residency, I plan to present two projects. The first is a series of watercolors based on my research into chemical elements and their connection to the human body. The second is a video project where I ask ChatGPT the following prompt: “25 Contemporary Art Project Ideas, Specifically Created by Artists from the Global South.” With this one I want to empathise in a humorous way the European gaze in the art world towards Latin American artists, there’s often this expectation that our work should highlight poverty, victimhood, or exoticism. While these themes are undoubtedly valid, they also carry the risk of becoming clichés, and for many of us they can feel limiting.

How do chemical elements relate to the human body in the materialization of your work?

I work with the elements of the periodic table with a holistic perspective. I’m fascinated by how chemical elements connect the human body with both living and non-living organisms. Our bodies are full of these elements: iron in the blood, calcium in the bones, copper, zinc and others in smaller amounts. The lack of them affects the balance in our bodies. Objects around us are also made of the same elements, which means that the possible relationships between everything are endless and often surprising.

One of my favorite elements is lithium. It’s used in batteries, but it can also be prescribed for bipolar disorder. That duality says a lot about the subjective and complex role of these elements in our lives, and about how they’re tied to the way the world is organized politically and economically. We as humans tend to think of ourselves as something separated from the world around us, but in reality, everything is interconnected, belonging to a much larger web.

My work with the elements is an attempt to tell their stories: what they do, how they transform when treated in specific ways, and how they act within different practices. Sometimes my approach is more physical, other times more conceptual. For example, I’ve made body sculptures out of coal, but I’ve also created a short film inspired by nitrogen. The piece recreates a parallel future where suicide by nitrogen—often known as “the sweet death”—is socially accepted. It was a way to reflect on both the material’s properties and its psychological implications.

In your practice you explore ways of expressing and externalizing psychological illnesses. What limitations do you see in contemporary social and artistic approaches to these subjects?

Artistically, I think these themes have started to be explored more openly in recent years, which I see as a positive shift. Bringing them to light helps to break down the stigma and taboo that often surround them and makes it easier for people to relate with it.

Socially, I think we still have a long way to go. Mental and neurological conditions are often treated as something abnormal and people experiencing them can easily be marginalized or judged. But most of these conditions come from imbalances in the chemical processes of the brain. Again, the elements are present here. If we collectively understood the close interaction and co-existence between humans and all elements and organisms around them, we’d have more tools—and more compassion—for addressing these realities.

Interview Vanesa Angelino (@vaneangelino)

Photos Leon Lafay (@leonlafay)