Meet the Artist // Paula Garcia Sans

Paula Garcia Sans is a visual artist born in Barcelona and based in Amsterdam. In their artistic practice they explore the uncanny through digital tools and sculpture, using mediums like stone, wax, 3D software and game engines. Strongly influenced by sci-fi narratives, their work captures the tension and blurred line between the artificial and the natural based on their daily observations and personal experiences.

Could you tell me about your background and the project you are proposing for this three-month residence here at GlogauAIR?

I studied in a university of Fine Arts and Design, specialising in audiovisuals. The department had a broad view of how to work with fine arts, even if my practice was more video, I could work with anything else. This is how I started working with sculptures, and trying different materials. I became interested in materials used in modern technology, such as silicon, latex, or thermoplastics, which are the materials to make robots that resemble us. Later I realized that these materials expand and contract a lot, that’s how I came to work also with glass, which when hot can also expand and then it can be reused. Then COVID started, I couldn’t access my studio in the university and I had six months before graduating to present my project. Since I couldn’t work materially with my hands, I started working with 3D software because it was the only way I could reproduce the abilities and capabilities of these materials on a computer, and I could even make it interactive. So I ended up graduating with the creation of a video game, not with sculpture. After that I stayed fascinated with the idea of 3D software because you can do anything in 3D.

During the past four years I was immersed in learning 3D software in the Netherlands, where I also started working professionally as a 3D artist. Recently I’ve gotten back to sculpture and I’m planning to integrate both in my practice.

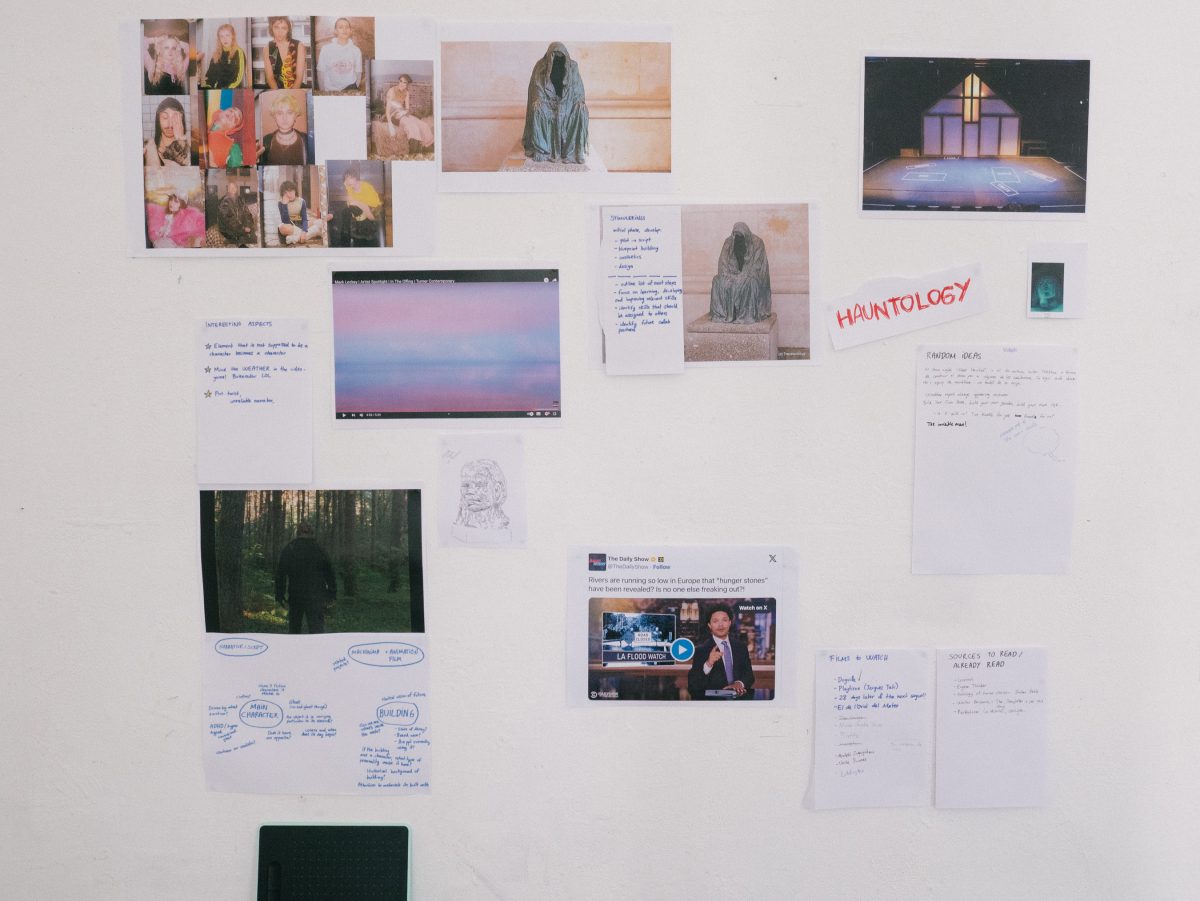

For my project in the residence, I’m working on a video game which is situated in a village flooded by the regime of Franco in the 60s in Catalonia, which after a long period of drought became visible again in 2023. That is when I went to the village, documented it and now I am working on this video game with the 3D scans of its remains as a background. You as a player –a ghost– have the possibility to go around this village, which is now underwater again. I want to develop the plot of this video game for an art exhibition context, nothing longer than 10 minutes. At the same time, I want to present in my room for the Open Studios a material installation inspired by the concept of the video game. I will work with wax and stones, materials that for me recall this ghostly spirit and also appear partially in the video.

During the residency, you’re developing a multimedia installation set against the landscape of the ruins of a flooded village in Catalonia, which you personally documented during your visits there. What initially drew you to work with this place?

I’m usually drawn to the uncanny, and water reservoirs have always attracted me because there’s something artificial about them, yet it’s hard to pinpoint exactly what. Back in 2023, talking on the phone with my parents while I was in Amsterdam, they said that Catalonia was experiencing a severe drought and that they were enduring water restrictions due to its high demand because of the heat. When they mentioned the resurgence of this flooded village, I decided to visit the zone. In my research I discovered that the water reservoir was built by prisoners from the regime of Franco, but before many people were living there, and they were given a very small amount of money to move somewhere else. I went to visit the area a month after the ruins resurfaced, and it was quite shocking to walk around the village, it was many layers of history over history, from the past and from the future.

During my research I also got to know about the hunger stones. Long ago in Europe, inhabitants or people working in agriculture would carve into stones in a river during droughts to mark the water level as a warning to future generations that they will have to endure famine-related hardships if the water sinks to this level again. I related this concept to the village as it carries a similar message than a hunger stone, whenever we can see these ruins again, it’s a sign that something bad is going on.

At a time when the boundary between the artificial and natural is becoming increasingly blurred, what is your view on technological evolution and how do you interact with this context?

On this topic, I hold two very different points of view. On one hand, I’m highly critical of the rapid progress of technology, which feels out of sync with the natural tempo of human life. On the other hand, I enjoy playing with this concept and exploring the poetic possibilities of technology. Art is a place where to speculate with it, with different consequences from those of “real-world” applications.

Last year, I became obsessed with artificial intelligence and how I might use it in my own practice. I did a lot of research, listened to many podcasts, and tried to keep myself up to date with the latest developments. I even attempted to code my own generative adversarial network—a program that allows AI to create images and videos. I managed to write a little code, and at first I was totally thrilled. But after some time I felt that what I was doing wasn’t healthy, and the process seemed endless, so I couldn’t keep going. I also realized, after the initial excitement of seeing my very first AI-generated images, that everything else started to look the same. Even my friends, or people on Instagram, were producing similar results. That’s when I decided to return to the tools I already knew: the 3D software I had spent five years studying, and materials like wax or stone, which allow me to work with my hands. Technology can be overwhelming. If you’re constantly trying to stay up to date, you end up missing out on so many other things—because it demands that you spend your entire life in front of a laptop.

For your current project at GlogauAIR, you’re exploring the themes of past and future through the lens of “hauntology.” Could you elaborate on what this concept means to you and why you chose it as the central focus of your work?

This term came to me after visiting this village in Catalonia. It refers to how the past influences the present and continues to haunt us. When I think about Spain, I often hear people say: “Yeah, but Franco died in 1975, so nothing of him remains today.” The reality is that he and his legacy are still present, and that is a significant part of the Spanish social context.

Hauntology is often associated with something negative, most people think of scary ghostly presences when I mention this concept. But it can also be connected to positive experiences or legacies from the past. I try through my work to move away from the terrifying connotations people usually attach to ghosts. I get the sense that a lot of this negative association comes from British culture and the ghost stories of the Victorian era, which were used as a metaphor to critique social pressures and anxieties of the time, carrying a torturous connotation. But back in time, ghosts were not necessarily seen as frightening. The stories evoked ancestors, the Holy Spirit, someone who is always close by to protect you, or the presence of a loved one who, after passing away, returned as an angel to check on you or simply keep you company.

Interview Vanesa Angelino (@vaneangelino)

Photos Leon Lafay (@leonlafay)