Meet the Artist // Olivia Johnston

Olivia Johnston explores chronic illness, trauma, and sacredness through lens-based imagery, installations, and sculpture. Her work, exhibited nationally and internationally, casts around questions of identity, beauty, and community.

Tell us a bit about yourself and your background. How did you get into art?

I am Olivia Johnston and I’m from Ottawa, which is the capital city of Canada. I am primarily a photo based artist who’s moving into sculpture and installation.

Basically I’ve always been in art, I was a classical cellist for most of my childhood. I started playing cello when I was five. So, I spent a lot of time in the arts around artists, but mostly within the classical music realm. Then I went to an arts high school, and that’s sort of when I was introduced to photography. I haven’t really stopped since. I was shooting a lot of digital to begin with. My mom suggested that I take evening classes when I was still in high school.

And I also started working at SPAO which is a photographic art center in Ottawa. And then I also finished a degree in art history.

By that point I was in my early 20s and kind of a working artist.

Even though I was surrounded by arts and artists my whole life, I think it took me a while to understand that visual arts were a way of existing in the world. It was a “viable” career path.

In arts, you have to prove yourself through a portfolio and showing your work, which in Ottawa is not easy, because it’s a pretty small town, despite the population. It’s a more conservative town in terms of being culturally open. It’s a tough road.

So, I’m very happy to be here in Berlin where it’s extremely open and there’s just so much art happening constantly.

Do you have an anecdote that really stands out to you?

I think the transition into art, as opposed to classical music.

One person who really stands out is a person who was my mentor at school. He’s really just amazing at making people be aware that they are artists and know that they have a story to tell. I think that was really important to me early on. In my late teens it was important to know that I had a voice. He encouraged me to share my vision

Actually many people have helped me through my artistic journey. One of my best friends, Jen, who I have worked with a number of times, is a real inspiration and I think she’s part of the reason why I never stopped making work. I think that’s something that happens a lot: you go to art school and then you stop making art. That’s where I think a lot of people quit.

Jen was part of the reason I kept making it. She said “we are going to make this project” again and again. It didn’t have to be a big conceptual thing, although we have done that too. It was really about just making for the pleasure of making and making because we get enjoyment from it.

Can you go a little deeper in your practice? What inspires your work?

My practice was heavily photo based for 10 years.

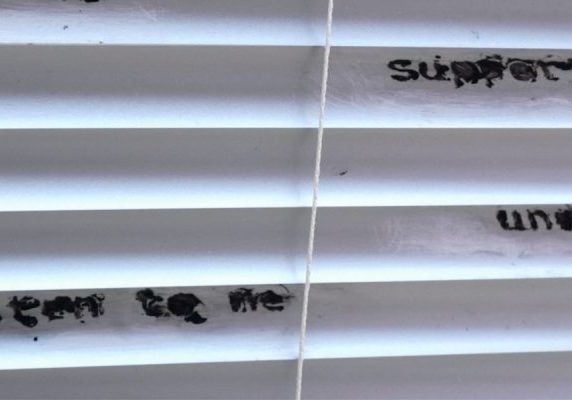

Photography is so much a part of our culture and society that kind of continuing to just make images and put them on the wall without any kind of mediation was not going to be helpful for the viewer. And I wanted people to start thinking more critically about images, because I think that that is something missing in society. Usually, people absorb images without question. I was interested in changing the image so that viewers are stopped before they have a chance to believe that it’s reality, I guess. That’s still part of my practice, but it sort of shifted into this idea of adding to the image to interrupt viewers’ understanding of it as a pure representation of reality.

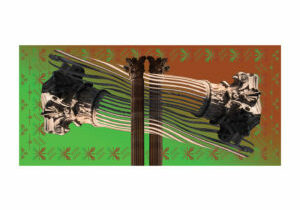

I would work with diptychs, triptychs and pairing images, using different formats to remind people that what they were looking at was an image and not reality. Then I started working with a CNC fabricated frame: it’s almost like a 3D printer, but with wood. You can cut out anything in wood that you want. I started thinking about frames and I was thinking about this because obviously art history was present in my mind. I had always been really compelled by medieval representations, specifically Northern European artworks from 15th and 16th centuries. Obviously, those images are basically always of the Virgin Child or Christ. They were taken from Catholicism, Christianity. The frames were always really elaborate. I was already making this portraiture work that was sort of painterly in nature already. All of those interests went into this one place where I was making these portraits of people as saints, as Madonnas, and fabricating these frames that were integral to the work. They were actually in fact part of the work because I designed them, and I hand gilded them with this imitation gold leaf. So it’s a meshing of a whole bunch of things I was interested in, in terms of adding to the image to make people realize that it’s art. There’s this sort of play between photography that is almost low culture since the common feeling is that everyone could do it and the so-called high culture where painting is like the ultimate form of art.

I really found I was interested in this idea of Catholicism as well. The Virgin Mary is somebody who’s been constantly popping up in art history. I wanted to convey this idea that she’s one of us. Specifically through this channel of art history, as opposed to the Bible itself.

Of course, the two are interwoven. But I was really interested in this idea that within art history, she’s depicted in so many different ways and we accept that as a society. But in a photograph of somebody, you’re able to recognize that one person is its own person. And if you see another photo of someone else, you wouldn’t be like “oh, is that also this person?” It’s a weird thing. We’ve kind of tricked ourselves into thinking about it that way.

There’s also the feminist underpinnings of it, too: she’s white, she’s a mother, she’s all these really pure, unattainable things for actual women. There is this idea that women can either be one or the other, saint or sinner.

You are now using many found objects, trinkets, memes in your work. What about the value that appropriation has in your practice?

I was thinking about whether I should be crediting the makers of the memes this morning. I went to see a show with an entire huge massive wall of memes, all credited.

I was thinking low meme culture is just the sharing of it. One of the memes that I have is like a repost of a tweet. So it’s sort of cyclical.

It’s interesting you ask about that because I think I haven’t really played that much with appropriation, although you could argue that by using images, I’m reappropriating or by using objects out of their original context.

I think appropriating goes along with this idea of the photograph in culture. Maybe the really true foundation of my work is thinking about photographs and images in culture and how they’re used and what gets people excited about them. When you take a photo, you’re kind of appropriating a piece of the world. You’re taking something from the world out of its context and putting it in a new context. It’s all about recontextualizing.

I remember going to this talk by an artist and she’s interesting because she’s a photographer. She makes sculptures out of other images, like magazine cut-outs, and then she photographs the final object. Is it still in relation to its original context? No. But is it still meaningful to that? In some ways, yes.

Taking something out of its original context and replacing that, I think there’s something really interesting there. And that gets me excited.

That is like what we do now. We just constantly think about self-referencing, self-awareness, with an ironic approach, almost everything is satire.

And this is also meme culture, basically. Memes are just like images being reused and reinterpreted and re-understood. It’s a way that we’re trading information.

How do you position yourself in the art world? What is your relationship with the art market?

I was part of an auction back home and my piece sold for above the minimum bid. So, people like my art. But it’s interesting, especially in a city like Ottawa. In Berlin, there might be different opportunities in that regard. I’m not that interested in the commercial world. I’ve sold a fair amount of work. I’m not going to say that I haven’t sold work. It’s just not really my interest. My aim is to show work publicly and for people to get to engage with it and have conversations about it. I think that’s my goal.

Do you think that art can also produce some changes?

Yeah, I mean, social justice and those realms have always been really important to me.

It’s hard to be up there right now and witness everything that’s going on and be like in my studio looking at my funny little things. But I do think that art can and has absolutely manifested change in the world. It would be silly to think that it hasn’t.

So I do think that artists have a role in changing the way people see stuff — social issues, each other, culture. I want people to engage with new ideas. And I think art is a really amazing way of getting people to engage with new ideas. You tell stories through images.

To get through to somebody with an idea together with something that’s visually compelling and exciting to think about, that’s really what I’m interested in. I just want to have conversations with people. And art is a really fun way of doing that.

I’m interested in ideas around chronic illness, disability and mental illness as well. Those are really important to have conversations about because it’s often really depressing and making it into something that’s a little bit more accessible for people than just a statistic or information. To humanize it and make people have a bit more empathy through images, through objects. I think that’s important to me as well. There’s a connection there too to the religious or Catholic stuff that I’m working on, where we find this idea of the Madonna and her son experiencing pain or suffering. So I’m interested in those as icons of illness, mental illness, physical illness. Pain is something we all can relate to.

Why did you join the residency?

My whole life kind of changed really quickly within the course of a year. I was living with my partner and we broke up. I thought I was going to move to Montreal to do a master’s degree and I did not get in. So I was like “well, I’m quitting my job and I’m going to go to Ireland to do a residency there”. And I did that. I found out I got into GlogauAIR at that time. I’ve been to Berlin several times. It’s an amazing city in its history, in the sort of dynamic of new and old.

As an art historian, you can’t help but be obsessed with new and old, even contemporary art versus the Bode Museum and Altes Museum, for example. To get to experience all of it while being surrounded by artists is very exciting, especially at this turning point in my practice where I’m thinking about objects more. I’m thinking about the internet more. I am thinking about installation and how images and objects together can shift people’s ideas about themselves and the world.

It’s great to go to the contemporary museums because there’s so many people there, but the older museums are often really quiet, similar to churches. I think there’s a lot more relevance to the museum than we can imagine. It’s just that they need a total overhaul that involves intersectional approaches to feminism, colonialism.

Berlin, obviously, it’s amazing. I’m very, very grateful to be here and be working alongside all these talented people.

What about afterwards? Do you have plans?

I do have plans. I would love to stay in Berlin, but unfortunately I cannot because I’m starting an MFA in the fall in Ottawa. So I’m excited to just keep thinking about the things that I’m thinking about now in an MFA context.

I’m going to be teaching a darkroom class, I think. So more of this, but in Ottawa. Which is interesting because it’s not exactly the same context. There’s lots of cool art people in Ottawa. It’s funny because I really know the community there. So it’s a very different environment. Coming to Glo after being in Ottawa for basically my whole life feels like I’m an emerging artist again, which is really interesting. Nobody knows me here. So I have to prove myself again and be my best self in every opportunity. I think it’s a question of getting situated in this new aspect of my practice, these new ideas.

I’m obviously getting so much from this and I’m sure 100% that I’ll be back.