Meet the Artist // Neda Kovinić

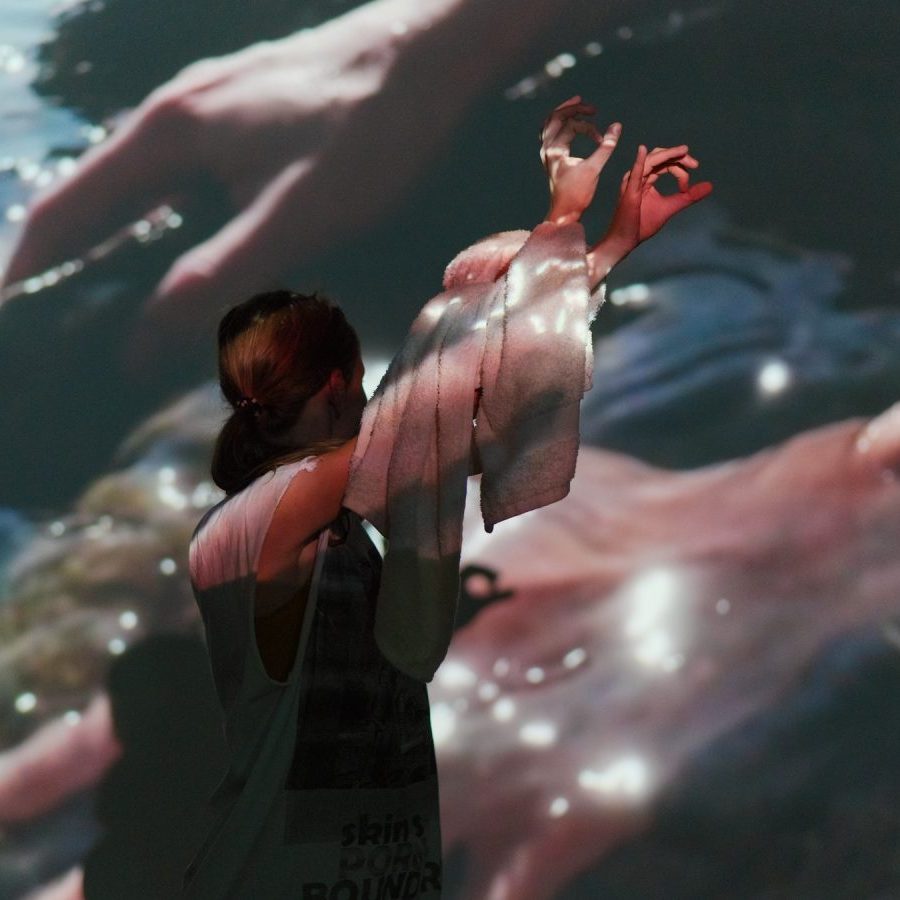

Neda Kovinić’s practice focuses on the intersection of body politics, social relations, and ecology, examining how these elements shape our movements in space. Her work responds to contemporary crises like the climate emergency, political disorientation, and ongoing conflicts. In contrast to these “dark sides of contemporaneity,” she advocates for creating performative communities through collective research and a processual approach.

Can you give us an introduction about yourself and about your practice?

I’m Neda, a research-based artist working across various mediums, including installation, filmmaking, and performance. I was born in Belgrade, in what was formerly Yugoslavia, and I completed my Master’s and PhD in Belgrade, Serbia. I am currently living in Berlin and aiming to relocate here permanently.

My experiences growing up during the 1990s, amidst wars, bombings, isolation, sanctions, and major crises, have deeply influenced my art practice and life path. Today, thanks to my artistic endeavours, I am fortunate to live and work in Europe.

In response to the crisis we face, such as ecological and political issues, as well as ongoing conflict, I focus on creating artist communities and collaborating with other artists. I share my resources and opportunities—such as exhibition budgets and gallery spaces—with emerging or less visible artists.

Initially, my work centred on installation, object art, and filmmaking. However, I later shifted towards live art, aiming to create and produce meaning directly within gallery spaces and museums. This shift also allowed me to further support younger and independent artists.

Through performance art and community collaboration, I address these crises by engaging in micro-politics, exchanging knowledge, and working collectively. My artworks manifest in various forms, including live performances, installations, experimental films, and research-based work involving text, drawing, and photography.

Tell us more about your fascination with the Freikörperkultur?

I’ve been exploring this topic for the past two or three years. It started in 2020 when I went to the Croatian coast with some friends during the pandemic. Everyone was seeking secluded places to escape, and I wanted to experience nature and more rugged terrain.

I recalled from my childhood that FKK (Freikörperkultur) beaches—nature-rich, clothing-optional beaches—were some of the best. However, when I arrived, I found that a well-known FKK beach had been repurposed and was now occupied by mainstream tourists, with concrete replacing the beautiful sand I remembered.

I continued my search and eventually discovered a small, rugged area behind some rocks, where a few nudists gathered. This spot had a stunning view, beautiful nature, and was very quiet. Over the next few days, as I engaged in conversation with others there and read more about the topic, I realized that the coastlines of former Yugoslavia, including Croatia and Montenegro, had undergone significant changes since the 1990s. The number of nudist beaches had declined, and interest in this culture had waned.

This shift reflects broader political changes and the rise of conservatism and nationalism, moving away from the values prevalent during the Yugoslav era. For me, this topic is crucial because it illustrates the impact of political and governmental shifts on cultural practices.

Furthermore, I researched the origins of free-body culture or social nudity, which I found to be rooted in Germany. While it is often associated with former East Germany, its origins date back to the 19th century. It began with medical and hygiene approaches that promoted sun exposure and exercise for healing. This practice, with its social aspects emphasised by philosophers and medical doctors, has ancient philosophical roots, extending back to figures like Pythagoras, Hegel, and Goethe.

The evolution of this practice through different ideologies and political contexts is fascinating to me. I am also interested in its ecological potential and the reconnection with landscapes, nature, and the elements such as sea, sun, and skin.

Who are some artists which have generally influenced your practice?

Coming from Yugoslavia, I began exhibiting at the Student Cultural Center, a notable venue for conceptual art in the region. This was where Marina Abramović and her group were prominent, though I was particularly influenced by Neša Paripović.

In terms of 20th-century art history, I was inspired by Marcel Duchamp, as well as the Russian avant-garde movements, including Malevich and Suprematism. Joseph Beuys, who also visited the Student Cultural Center in the 1970s, had a significant impact on our conceptual art scene.

More recently, I have drawn inspiration from artists like Sophie Calle, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and Hito Steyerl. I am also influenced by the third wave of performance art, particularly choreography and dance performance.

I recently encountered a Romanian artist in Hamburg, whose name escapes me at the moment, but I also appreciate the work of Anne Imhof. I value the contributions of choreographers and visual artists who integrate dance and performance into gallery and museum settings, exploring multiple temporalities and landscape dramaturgy.

What is your relationship with the art market? What do you think about it?

So far, I haven’t been involved with private galleries or collectors. I primarily receive support from state-funded institutions and residencies, both in Serbia and across Europe, especially in Germany. This is my first private residency.

I’m inspired by this residency, particularly the place and the team running it in Berlin. Being in Berlin is crucial for developing my current project. Although I hoped for funding, I was not successful in securing it. However, my upcoming funding will come from the Netherlands through the European Pavilion, as well as from German and Romanian sources.

Regarding the art market, I don’t engage with it and don’t share its values. The art market often evaluates artwork through a monetary system rather than focusing on the cultural meanings and content that artwork can produce and how it is perceived culturally.

How are you living with other artists here in GlogauAIR?

Living with other artists at GlogauAIR has been amazing. I truly appreciate being in artist residencies, and this one has a distinct Berlin spirit. People here are very relaxed and chilled, which is quite different from other residencies I’ve experienced. For instance, compared to another German residency, this one feels much more relaxed and joyful.

I’ve had the opportunity to engage in many dialogues and exchange information with fellow artists. We’ve had reading sessions together, and it’s interesting to note that a few of us chose the same book to read. Despite coming from different countries and generations, we share many common interests and readings. This experience has been highly educational for me. I really can learn a lot here.

You’re moving to Berlin, right? How do you feel that Berlin has influenced your practice?

I feel much more encouraged here to experiment. There seem to be no taboos and nothing is censored, except, of course, I’m really disappointed that I arrived in Berlin, Germany, during a time of political censorship. I had imagined absolute freedom in expressing thoughts and being critical of governmental decisions, but that hasn’t been entirely the case. However, on many levels, there is more freedom to express, experiment, and discuss. There are many people to learn from, and Berlin offers great galleries, institutions, festivals, and discursive events to attend.

What are your plans besides living in Berlin after residency here?

I have a very packed schedule for the next month. Right after this residency, I’m going to Bucharest to work on a project about censorship and the history of dictatorship in Romania, as well as examining the governments of former Yugoslavia and how democracy is understood today. This is a two-month project.

Another significant project is with the European Pavilion, titled Liquid Becomings. This project involves four floating pavilions with a group of artists who will sail on the Danube, Vistula, Tagus, and Rhine rivers. We will spend two weeks exposed to the rivers, sailing, living together, and creating artworks while reflecting on the concept of Europe and its future.

It’s really exciting. I’m also working continuously while I’m here.