Meet the Artist // LiLi 丽丽 Nacht

The work of artist educator LiLi 丽丽 Nacht is rooted in meditation, ritual, Daoist/Buddhist practice, and 山水 (mountain water) ink landscape painting traditions. LiLi 丽丽 creates environments by employing a diverse range of media, including painting, performance, and social practice to explore the tensions between chosen and inherited identities.

Can you tell me about your background and the project you’re proposing for this three-month residency at GlogauAIR?

I’m a visual artist and educator, born and raised in Memphis, Tennessee and Wuhan, China. This gap between cultures is quite vast, and dealing with these differences is what brought me to a creative practice.

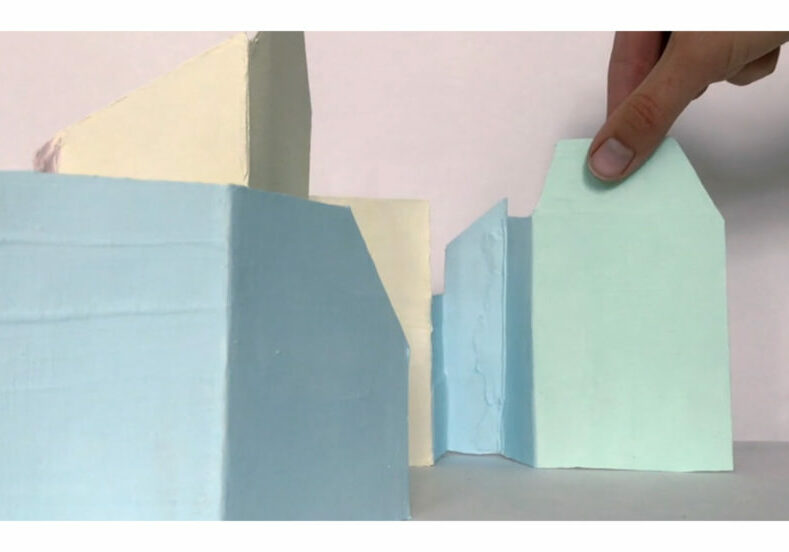

During the GlogauAIR residency, my project has become a research deep dive into I Ching, which is an ancient book of wisdom and oracle tool from thousands of years ago, Dao De Jing, one of the foundational texts of Daoism, as well as the compositional element, liu bai, or “leaving white”. Liu bai is a technique from the Chinese shanshui painting tradition, where emptiness is intentionally used within the composition to represent a space where you can project your imagination. I am also thinking about the correlation to Taiji Quan movements. There’s actually a lot of overlap between these different texts and practices, and they all inform each other.

What role does the body play in the creation of your work, particularly in relation to meditative movement?

As I’ve been learning Taiji Quan with my teacher Lingji Hon, who comes from a long lineage of Taiji Quan masters, I’ve been trying to channel the qi, or energy, moving through the body into the work itself. Letting the movement influence the forms that come out. Shanshui painting doesn’t emphasize visual accuracy as much as capturing the inner essence and life force of the subject–the feeling you have while creating. A movement practice really pairs well with this.

Previously, performance has been a crucial part of my work. This time, I’ve decided to focus more on the visuals as the creative output, informed by historical research and Taiji Quan practice. A lot of these images stem from specific movements or I Ching hexagrams. They’re not just random shapes and abstract forms. I’ve been struggling a bit in communicating this, but I think if people can understand that the work is created through an exploration of movement and energy, it helps give more context.

In your artist statement, you mentioned a desire to foster collective unlearning. How does this intention manifest within the specific project you’re developing during the residency?

During the residency, I’ve also hosted a few workshops. I’m very interested in social practice and using art as a tool for bringing people together in addition to having my own studio practice. Together with Tofu Stand Collective, we organized a tofu-making and puppet theatre event sharing the story of how tofu was brought to the West by Chinese anarchists. This past Sunday, I hosted an I Ching workshop as well. All of these are dealing with knowledge that is passed down between generations. A goal of mine is to provide diasporic people with opportunities to understand the wisdom of their culture more in depth and to develop practices of resilience within the community.

Specific to the works here in the room, I’ve been learning a lot from I Ching and Dao De Jing. There’s so much depth to the words. These learnings have changed my mind about my process and even about the world in general. It’s taught me to be more humble and accepting towards life. I am certain many people would benefit from these ideas. Unfortunately, I think the wisdom of these texts can be difficult to access without guidance or studying. I wanted to create an environment and visual representations that offer an entry, without having to read, read, read. Maybe it’s a universal feeling that can be transcribed regardless of language.

About “unlearning”, I mentioned earlier that I come from the American South and also from Wuhan, China. Living in Tennessee, I hated being Chinese and suffered from a lot of internalized racism; my heritage is what marked me as different from my surroundings. When I was in China, I was also treated as though I’m not from there. I developed a superficial and kitschy understanding of Chinese culture “oh, there’s this dragon scroll or Kung Fu characters in a movie”. It was passed down to me through consuming media that wasn’t authentic or intentional. Now that I’ve taken time to really understand the history, texts, movements, and philosophies of the culture I’m from, I’ve gained a whole new appreciation. I’m no longer constantly negotiating with the world my right to belong. The process of unlearning is crucial, because as we become adults, we have to decide what opinions are our own and what beliefs are inherited from the environment where we grew up that no longer serve us. That’s what I mean by unlearning. I didn’t even know how to pronounce yin yang correctly for a big part of my life, let alone understand that it represents an entire belief system.

How do you navigate the tension between the traditional and the contemporary in your practice, and do you aim to preserve ancestral forms, or do you reimagine them from a critical and personal perspective?

I’m interested in what is simple and what endures. Tradition gets a bad reputation, because it often becomes conflated with nationalism, or it is used as a reason to ostracize. It is misunderstood, because it’s not current or it is presented outside of context and cut off from the true meaning (think yin yang symbols on merchandise). I do believe there is a lot of knowledge held within cultures that should not disappear; there’s a reason why some things have been done a certain way for centuries. Of course, there are aspects of tradition that have to change, and we have to move with the times. Lucky for us, knowledge has a way of disappearing then remerging as we move through periods of peace or periods of distress. The past years have been very difficult on the global scale, and I think now more than ever we must lean on this collective wisdom held within our histories.

How does it fit into the contemporary context? I’m very interested in how diasporic people who have left home for whatever reason–war, forced migration, searching for better opportunities–embody this new hybrid knowledge that is formed in the process of uprooting and building a new home. That’s where it gets interesting. How does this synthesis of information happen within someone’s life? With unlearning, it’s important to recognize the context of where you’re from, to be able to know where you’re going. To live from a place of true understanding, because if you don’t, you’re hiding from a part of yourself.

What role does silence play in your creative process, and do you see it as an active tool, a compositional element or a necessary framework for the project you’re working on here?

Yes, absolutely. Silence can be understood as emptiness, or a manifestation of yin energy – a pause or retreat. And as I’ve learned from I Ching, emptiness can be seen as receptiveness. It allows for something to come in. Within this philosophy, the binary is not really a binary. It’s more like two counterbalances that together form a whole. A valley is empty, but it is the most fertile land because it allows for water to enter, allows for life to enter, and in doing so becomes full. So, silence is something that holds everything else around it. Emptiness within a painting or an artwork holds the rest of the composition in balance. By lui bai or “leaving white”, you create space for contemplation and allow the mind to wander to other places beyond the surface of the canvas, maybe even beyond the room. And I think this liminality is very beautiful.