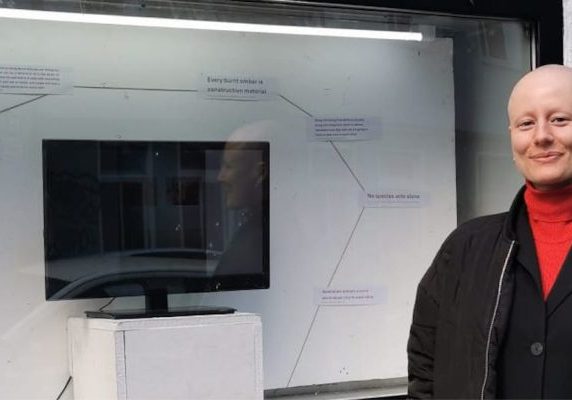

Meet the Artist // James Lemon

James Lemon, born in 1993 in Aotearoa (New Zealand), has been based in Naarm (Melbourne), Australia, since 2012. He’s a sculptor with a focus on clay. Lemon explores clay’s historical and ecological aspects, looking into its role in developing civilisations and connecting with other life forms.

Lemon’s work evokes religious elements, pop culture, and insects. While clay is his primary medium, Lemon often adds unconventional elements like bricks, precious stones, and discarded items to enrich his artistic language. His ongoing project, “SPHEXISHNESS,” addresses ecological concerns, specifically insect population decline and climate collapse. Through intuitive making, Lemon’s sculptures act as memorials for declining life forms, offering a commentary on the interconnectedness of human and natural worlds.

Can you give us an introduction about yourself and tell us about your background?

I’m James Lemon. I am an artist. I work mainly in sculpture and ceramics. I was born in a small town called Te Awamutu in Aotearoa, New Zealand. I currently live in Narm, Melbourne. That’s where most of my practice takes place.

I came to ceramics in 2015 making functional ware—cups, bowls, and objects for the table and food sharing. That was a way for me to gain a skill set using the material and understand the different intricacies of studio practice and how to support it through some bread-and-butter means.

After a while, I began producing what I wanted; I’ve been making my work for about seven years now.

I recently had my 4th solo show; it’s gorgeous to be working with Oigall Projects which the commercial gallery in Melbourne I work with. Andy is one of the most ridiculous people I’ve met—extremely fashionable, exceptional taste. He gets me (gay guy).

Tell us more about your fascination with apocalyptic scenarios and how you integrate that into your practice.

I was introduced to the apocalypse from a very young age. I was raised in a Pentecostal environment, unlike your usual Catholic Christianity. It’s your Bible-bashing Baptists; you see them on the news in America all the time. It’s more aligned with cultish practices; it’s a lovely authoritarian system.

I remember reading the Bible from cover to cover and lingered for a while on the Book of Revelation. I found it darkly tantalising.

I got wrapped up in the fantasy of life after death, balancing a deep fear of death with a fascination with death as a potential journey or realm. This perspective can make current reality seem less significant to those who prescribe this fantasy.

The rapture depicts a horrible doom; I find it fascinating and aesthetically rich. Yet, Pentecostals are very horny for the rapture. This fascination influences governments (listen to politicians in the USA talk about this, for example) to implement policies around these apocalyptic beliefs. These policies are a precise intersection of religious beliefs and political dynamics. They use prophecy to justify violence—the Israel-Palestine conflict as an example. Beyond the colonial forces at play, a spiritual war is beneath the pursuit of power. For many in the faith, what’s unfolding is understood as a fulfilment of prophecy. Unfathomable death is all part of his plan, and they cheer it on; they take comfort in it. My fascination with the apocalypse can appear untethered from reality, but it’s really not—climate change is the other thing.

My work draws from apocalyptic imagery, I use tombs, urns, and death objects. I reference religious iconography and build like a termite chewing up left behind objects.

What are some artists who have greatly influenced your artistic journey?

Adrián Villar Rojas. I’m obsessed with his work. He makes these insane sculptures. I initially found his works were large raw clay sculptures made in a forest that would disintegrate into the environment.

His practice involves creating forms that might be discovered by a future civilization on Earth, uncovering artefacts of our society and what they look like. He did this incredible exhibition at Sydney Contemporary in the new building, which looks like a Berlin space. It’s a big oil tank, a cavernous hall. He made these alien blobs that look like machines in motion, but you can’t quite decipher the forms. That work actually made me feel something.

I think from a queer perspective, one of the first artists that influenced me was Robert Mapplethorpe. My art teacher, Mr. Jarry, introduced me to his work. Mr. Jarry was Canadian, a punk who needed to fit the schooling system. I think he saw something in me. I saw an exhibition of Mapplethorpe’s work once at AGNSW in Australia. I was sitting next to a lovely older woman, and both of us were captivated by the work of a pipe going into a body. Sharing a moment with this woman was beautiful; when I last saw this image, it was profoundly private and taboo.

On a personal note, a dear friend of mine is Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran. We’ve been friends for many years, and his wisdom has significantly influenced my practice. His support gave me the confidence to relax into my artistic intuition. We both work expressively in our medium, and his encouragement has allowed me to deepen my work and hone my artistic language.

Catherine Bell is another artist I deeply admire. Her work also centres around death and objects that observe and sanctify it. She’s so sick I’m obsessed with her.

Also Bjork. Max Richter. Azealia Banks, Nina Simone and Robyn.

How are you finding GlogauAIR now that you are a resident? How is it living with other artists?

My personal experience is that my usual studio at home is so well equipped. I have everything in my space: a kiln, all my materials, space, and also a place to do messy work because the way I work is messy. That’s how I achieve the abstracted or grotesque forms I play with—because I have room to be chaotic.

I found it quite challenging to work in the space I also have to live in. The materials I work with are not the safest for sleeping in those environments, which is quite challenging. Challenges and boxes around what you’re making can sometimes lead to diamonds, but I found it hard to work against this when it’s logistically quite tricky.

Despite the setbacks, I’ve managed to adapt and find alternative ways to continue my artistic journey. I just finished a large amount of work leading up to this time. My artistic practice is like a plant. It’s not always in bloom; it must die off a little, then seed, come back, and grow before it can flower again. I came here without energy, so finding my rhythm has taken me some time. I found a couple of nearby studios where I could make things and start that process. I went there for a few days, and then they went on vacation. That was a hassle. The other backup plans for facilities had also shut down, and I couldn’t use the kilns until October. My experience has felt bound, perhaps more than expected, but that’s good. A lovely new friend Jana Franckle let me use her kiln though which was very gorgeous and generous of her.

These setbacks also left me room to do what I love: dance. The role of music and dance in my practice brings me the most joy; I will be in my studio making works, slithering like a snake to ‘Gimme More’. So, I’ve been able to do everything else in my life that also brings me joy while I wait for more specific studio access. Before I even thought about art as a practice, it was music. If I had taken music seriously, I would be a musician now. Don’t make me sing.

I want to start embedding the music and finding ways to explore it but I think because it means so much I keep it at bay. There’s a lot I need to learn, but also a lot of material I have to work with as it is. My time has been well used being directed into slightly different directions than usual.

How is Berlin influencing your practice?

From what I said about the musical side, there isn’t sound infrastructure like this anywhere else. It scratches a part of my brain that I can’t get scratched back home. It’s not just the sound environment; it’s also the people who appreciate it and being in rhythm with them.

Australia has had some pretty bad vibes for the last little while. Arts funding is terrible. It becomes hyper-competitive. Your colleagues become your competition, and I think that stifles good work and makes people fucking nuts. The arts industry is fractured due to what’s happening at the moment in Palestine, coming to a place where those histories are much more present and charged might sound deranged perhaps. Sometimes, it’s garbage and chaotic; sometimes, it’s beautiful and eye-opening in good and bad ways. It’s more interesting than being in Brunswick.

I’m all about vibe contribution. If you’ve got something interesting, fun, or unique to contribute, it’s appreciated rather than gawked at. I feel calm here. I feel comfortable making work and being the faggot that I am rather than being the ‘corporate fit’ that I sometimes think some Australians want me to be. My work and my relationship with my fiance suffer under those conditions. I love this city. I think it can eat you up, but there’s much richness here.

What plans do you have after the residency?

I’ll be making some new work when I’m home, I feel very artistically nourished but I’ll be back, it’s a negotiation between visas and the right opportunities. The plan is to get here in the next 5 years, which requires a bit of planning. Boyfriend Bobby needs to sort his Italian passport first. My practice is so cemented back home and sculpture can be tricky. My work cannot simply be rolled up, put in a tube. Perhaps I should make some tubes.