Meet the Artist // Clara Silveira

Clara Silveira uses a variety of media in their work to explore the tension between fiction, reality, memory, trauma, and identity. Silveira seeks to explore the dark spaces that coexist between the intimate and public spheres, addressing themes of love, loss, femininity, and violence. Silveira intends to use the community as a driving force within her process.

Could you tell us a bit about your background and the project you are proposing for this three-month residency at GlogauAIR?

I’m a Brazilian multimedia artist with a nomadic background—I’ve also been a tango dancer for years, and that sense of movement and connection definitely seeps into my work. For this residency, I’m developing four projects that orbit the same themes but use different materials.

Recently I started working with a lot of perishable materials. One piece involves tiny figures cast in burnt sugar. For this specific piece, I’ve been reproducing two objects I carry with me: a toy soldier and a saint figurine, both found randomly on the street in Brazil. I took a few molds before coming here and now I’m reproducing these figures in sugar.

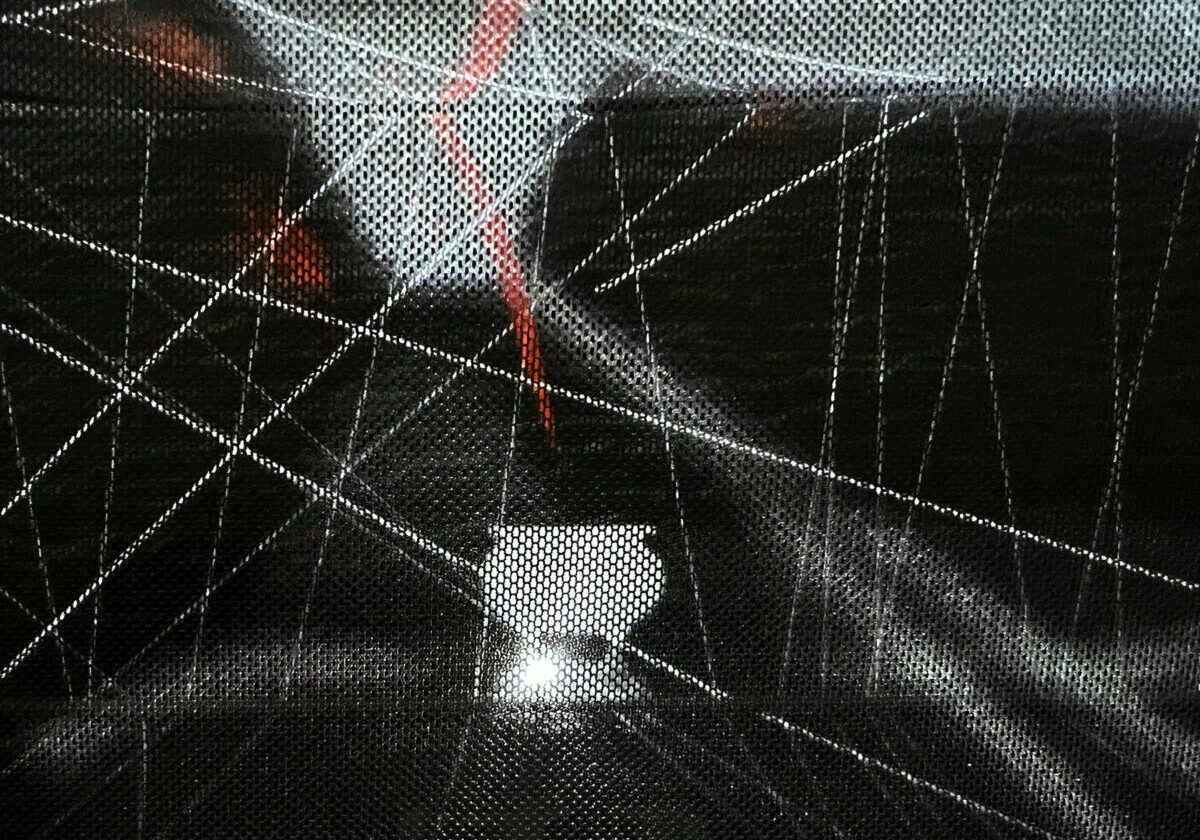

Another project is a net woven from human hair—my own, my mother’s, my sister’s, even strands friends donated before I left. It’s slow, intimate labor. I’m also working with fabric, using a technique called drawn thread where I pull out individual strands to “draw” absence into the material.

And finally, porcelain lithophanes—thin panels where images only appear when backlit. All these materials—sugar, hair, thread, porcelain—are about what lasts, what fades, and what we reconstruct in between.

Can you tell me a little bit about the subjects that you explore inside of your work?

Mainly I’m interested in how violence shapes memory. I focus on grief, loss, and domestic experiences – particularly those traditionally tied to femininity – and how they reshape the way we structure our personal histories.

I strongly believe the personal is political, so these intimate experiences don’t exist in isolation. They indicate wider social patterns and collective memory.

What led you to work with porcelain and lithophanes as a medium to explore memory and personal archives?

Well, first I thought it would be interesting because lithophanes were popularized by Germany, particularly by the Prussian Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur (KPM) in Berlin, in the 1820s.

They would often depict domestic or religious scenes. I very much like this resource, how the images conceal and reveal themselves depending on the light. It makes a great metaphor for memory. Every time you return to a memory, you’re reshaping and re-editing it. That’s why I think lithophanes work so well for talking about memory.

Your work seems to be shaped by processes of grief, loss and trauma. How do you transform these kinds of experiences into artistic material?

I think when you have a very intense experience – whether it’s grief, loss, violence, or even something sublime that’s happy in a way – whenever it’s too intense, it exposes a radical fracture between the experience itself and language. It resists articulation, but still it must be expressed somehow. I think that every time I’m working on a project, I’m trying to express it, understanding that I will probably fail on this.

Every time I’m working on a project, I’m trying to express that, while understanding I’ll probably fail. I’ll never fully capture it. But there’s beauty in this exercise: trying to articulate what’s unsayable – what can’t be contained in words or images. That attempt itself, trying to say what can’t really be said, that’s what drives the work.

In your work, fiction and reality come together. How do you balance these elements, and what kind of effect are you hoping to evoke in the viewer?

At first, blending fiction and reality was a necessity. Since I depart from personal stories, sometimes they were too painful. So fiction would help to dissolve the reality or even to hide real names or the rawness of what had happened. It was more like a very conscious choice to protect myself from excessive exposure.

Now, I use this approach differently. By creating intentionally unstable ground, I invite viewers to project their own experiences onto the work. There is a more flexible and interesting backdrop to work with. It also helps me to maintain things in a broader perspective.

Emotionally, it helps me maintain perspective, while allowing others to find their own connections. I wouldn’t call it universal, but it opens the work to multiple truths.

In your project, you mentioned that you don’t aim to shed light on the subjects you explore, but rather to inhabit the dark spaces between the intimate and the public. Could you elaborate on how you approach this tension in your practice?

Light is essential—both its presence and absence. It’s what makes the work work. My practice lives in that tension: giving form to experiences that resist being put into words, yet demand to be expressed. Memory itself is unstable—a landscape that keeps shifting. When I can’t pin something down as absolute truth, when it keeps changing, it transforms how I tell my own story, both consciously and unconsciously.

Light and darkness become metaphors for this duality: what’s known and unknown, what’s remembered and forgotten. There’s no universal truth—only facts filtered through subjective lenses. This resonates deeply with contemporary movements in South America, where we’re re-examining colonial histories, or grappling with today’s political chaos—fake news, AI-generated “truths,” and distorted narratives.

We’re in a very interesting and dangerous moment at the same time—one that demands a lot of critical thinking, historical context, and a lot of source checking and a historical perspective to understand things. My work inhabits that unstable space, where light reveals some things while leaving others in shadow.