Meet the Berlin Guest // Selma Köran

Selma is an artist of personified chaos—sculpting, claying, stop-animating, and hacking through digital and mythological debris. With Turkish-German roots in Berlin, she calls herself a dilettantish archaeologist, excavating collective memory, pop culture, and fictional ruins to rewrite power through feminist worldbuilding and glitchy counter-myths.

Can you tell me a bit about what you’re working on for your exhibition at GlogauAIR?

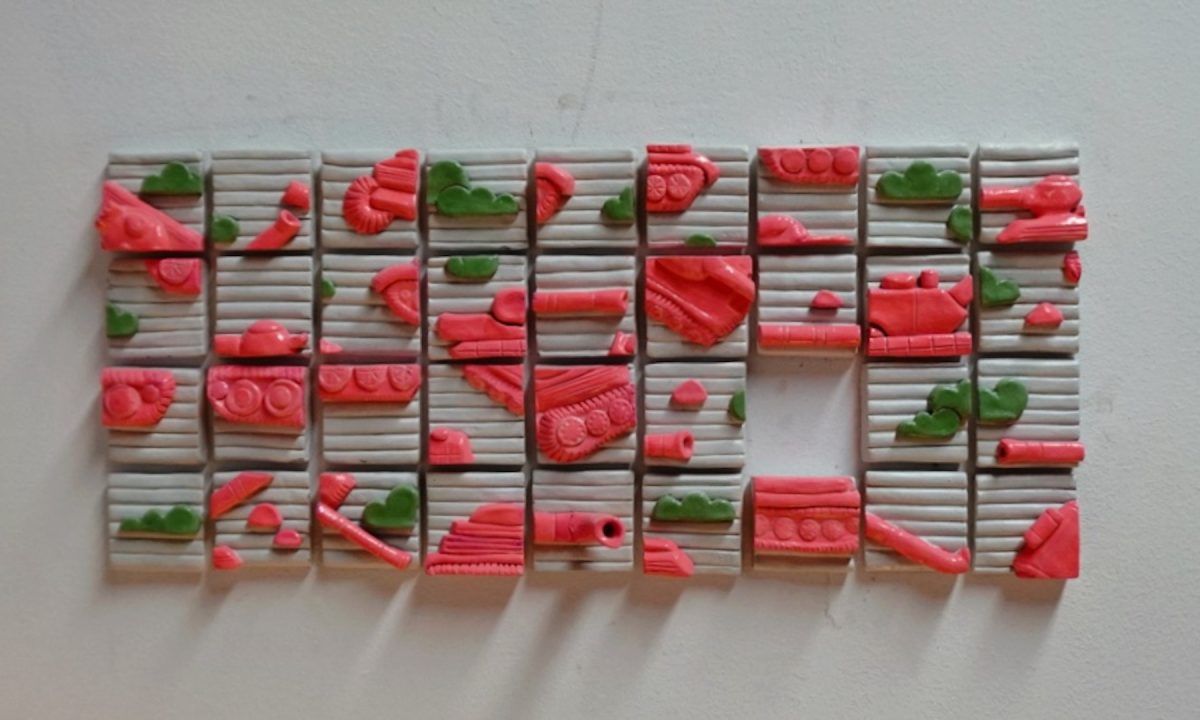

For the exhibition at GlogauAIR, I’m working on a series of game-based worlds and sculptural interventions that expose the choreography of patriarchal power through play. Instead of illustrating resistance, I’m building systems where dominance becomes glitchy, overacted, and structurally unstable. Myths, interfaces, and weapons are recorded until they reveal their own absurdity.

The keypiece will be a sculpture titled “Ayçiçek”, the Turkish word for sunflower, but it literally translates to moonflower.

It reflects on my identity of being half Turkish and half German. Should I look at the moon or should I look at the sun? And it emphasizes on the contemporary condition of womanhood: self-sufficient to the point of exhaustion, empowered yet continually burdened. Autonomy exists, but it exacts its price.

Can you tell me more about how your art relates to your identity and upbringing?

Identity wise, I think the most important thing is that I’m a female and this is universal beyond borders, so in general my work is informed by the struggles of being a woman. Then of course dealing with being Turkish in Germany, you obviously get thrown a lot of racism in your face. I like to shield that, so I build an armor of humor and I think it shows in my work.

How did you get into archaeology and Greek mythology, and how did that become so influential in your work?

For that I have to take you back to my childhood. The first book I ever got when I started reading was a Greek anthology from my grandfather. There was this little drawing of Athena, and amidst all the other gods – it’s just a little ink drawing – she’s standing there between Apollo and Zeus. They’re looking straight at her and she looks straight at you with her armor, but I always felt like she feels so uncomfortable in her position and I couldn’t tell why.

I devoured this whole book and I could not find a narrative about her that was satisfying. Later in school we had Latin, and Athena exists in Latin as Minerva, but back then there was no internet to translate all the texts. So I was super eager and super good in Latin for the reason of wanting to find my desired narrative for Athena, but I couldn’t find it. In my video installation, Exit Athena, I rewrote the script to finally set her free and to overcome Zeus and overthrow patriarchy. My extreme interest in mythology has been here all my life. I would describe it somewhat as my childhood psychosis.

I think Greek mythology still informs all the western morals. Historically, the figure of the dominant, all-powerful male deity has simply shifted its form. Zeus, who openly embodies rape, coercion, and violence, is replaced in later cultures by the idea of an omnipotent monotheistic god. But the underlying logic doesn’t disappear. The structure remains patriarchal, and the mechanisms of control remain almost identical.

How does your humor and your process come into play and what are you hoping to evoke from your audience?

My work comes from female rage. I think rage should be something that should not be ignored, but rather celebrated because all women are still educated to not to be so rageful and hateful although there’s obviously plenty of reasons to do so and resist the course of the patriarchal norms. It’s a heavy topic and that’s why I employ humor to make people laugh while simultaneously provoking a lot of people–I think there’s always split reactions. With my video installations and sculptures, either people really like it and they feel seen. Especially from girls or women, I always get a positive response. While old men usually tend to get rather angry at my work.

To be honest, I’m quite happy when I can make some white old man angry. I’d say it can be both laughter and anger which I want to evoke in people.

Interview Shay Rutkowski (@sruutrut)

Photos Yasemin Erguvan (@yaseminerguvan)