Meet the Artist // Dakota Guo

Dakota Guo is a Rotterdam-based interdisciplinary artist working across performance, video, installation, text, and sculpture. Her work explores ritual, liminality, and the ethics of relation between the living and the dead. Through layered visual language and fictional narrative, she examines how memory, ghostliness, and symbolic economies persist.

Can you tell me about your background and the project you’re proposing for the three-month residency at GlogauAIR?

I was born and raised in China, studied in the UK, and later in the Netherlands. I completed my bachelor’s degree in Drama and Theater Arts, followed by my first master’s in Performance Practice as Research. In 2022, I earned my second master’s degree from the Dutch Art Institute, a roaming academy dedicated to visual arts and research. I’ve been working across performance, video, installation, text, and sculpture.

In recent years, my artistic trajectory has centered around ghostly matters—navigating the realms of the living and the dead—drawing predominantly from Chinese cosmo-(necro)logy, funerary traditions, and ritual technologies from Taoism and folk religions. Two years ago, I initiated a research project titled Tools for Speculative Archaeology, which explores the symbolic and material exchanges between the realm of yin (阴间, the realm of the dead) and the realm of yang (阳间, the realm of the living). While archaeology traditionally engages with the past through excavation and documentation, my approach diverges significantly by questioning the ethics of intrusion inherent in such practices. Adopting the persona of a speculative archaeologist, I treat the excavation of burials explicitly as a form of trespass into the realm of the dead. This fictional persona appropriates archaeological methods—ranging from fieldwork and documentation to artifact handling and exhibition—not to possess or exploit, but to ethically engage with the deceased and to navigate contested issues such as decolonization and restitution from a perspective that prioritizes the rights of ghosts.

During my residency at GlogauAIR, I’ve been developing the second chapter of this research. The first chapter culminated in a 2024 exhibition focused on ritually repatriating a forged tomb document directly to the dead through an act of self-offering. In this second chapter, I am addressing fundamental questions of access, permission, and shared spaces between the living and the deceased. Prior to arriving in Berlin, I conducted fieldwork in Sichuan, China, where numerous Eastern Han dynasty cliff tombs remain openly exposed. Accompanied by my collaborator, 3D artist Hui Lin, I unauthorizedly entered two empty cliff tombs, performed LiDAR scans, and captured footage. At GlogauAIR, I have been analyzing this digital data and reflecting deeply on my firsthand, unsettling experiences through drawings and journaling. The speculative archaeologist persona continues to guide both my intentions and outcomes, clearly distinguishing my work from traditional archaeological practices.

What draws you to the visual language of archaeology, and is there something in the way it represents the past that you find problematic or poetically generative?

Yes, I think you summarized it really well. It’s both problematic and poetically generative. Archaeology’s visual language embodies a tension between meticulous preservation, rigorous documentation, and acts of intrusion or appropriation. For example, museums display spirit articles behind glass—labeled and detached from their original contexts. These beings wouldn’t recognize themselves in these environments, as their spiritual and symbolic attributes are never going to be accommodated in that way. While I find this problematic, it also intrigues me and prompts me to intervene in artistic and speculative ways.

visual language embodies a tension between meticulous preservation, rigorous documentation, and acts of intrusion or appropriation. For example, museums display spirit articles behind glass—labeled and detached from their original contexts. These beings wouldn’t recognize themselves in these environments, as their spiritual and symbolic attributes are never going to be accommodated in that way. While I find this problematic, it also intrigues me and prompts me to intervene in artistic and speculative ways.

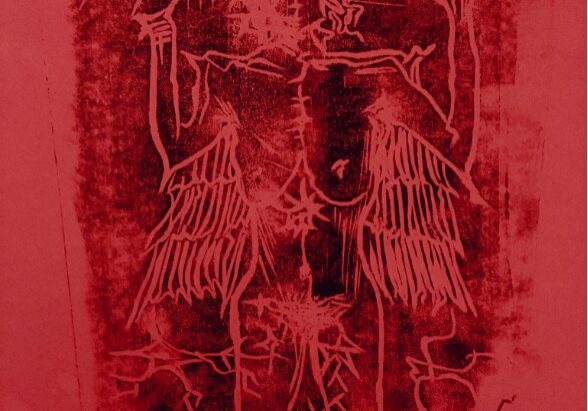

Working with ritual technologies and materials like joss paper, wax, and textiles, I attend to a sense of perishability in archiving. Since the speculative archaeologist is not going to unearth and exploit anything, I forge unearthed artifacts instead. For instance, during my residency here, I created 49 hanging folders using dyed and wax-processed fabrics, intentionally making them appear as if they had been excavated—creating a set of phantom archives.

Because my background isn’t strictly visual or archaeological, my works consciously and unconsciously contain many unpredictable errors. I’ve come to accept—and even embrace—my inability to achieve precise archaeological representation. My work neither convincingly mimics authentic ancient artifacts nor conforms to the conventions of legitimate archaeological handling. The ritualistic and ephemeral aesthetics take precedence, highlighting the speculative nature of the work and injecting a kind of irony or sarcasm into the approach.

You mentioned that you’re developing a speculative narrative during the residency. How do you go about constructing that fictional voice?

I’m still working on a script, trying to annotate my fragmented drawings and notes. My method involves blending fictional elements with real historical materials. I draw upon journals and logs from early Western visitors to the cliff tombs—mainly anthropologists and missionaries from the 1930s. I also refer to actual archaeological reports, though perhaps not those linked to the exact tombs I entered, as there are more than a hundred on the same cliffside, most of them barricaded after official archaeological fieldwork.

I compare these historical site plans and findings with my own LiDAR scans and digital data, using them as raw materials to speculate on the manifold entries to these sites—across two thousand years and the supposedly distinct boundaries of the living and the dead. I integrate personal, sensory experiences from my time in the tombs, speaking through the voice of my fictional archaeologist persona. At the same time, I attempt to evoke the imagined perspective of the tomb’s owner, highlighting a sense of domesticity. This is inherently speculative and delicate, as I don’t know the tomb owner—and I am also a trespasser. Balancing these perspectives without projecting too much or turning it into a romanticized ghost story is particularly challenging and central to my approach.

How do you balance respect for the sacred or ancestral with artistic intervention? And what strategies do you use to engage in a dialogue instead of appropriation?

Firstly, I don’t think complete avoidance of appropriation is possible. As a Chinese artist drawing heavily from Chinese heritage, I frequently feel I’m appropriating my own culture. Being Chinese doesn’t inherently grant me full comprehension—particularly when engaging with Taoist texts, where my understanding is minimal. Yet, my cultural identity often grants me a perceived legitimacy or entitlement to do so. In my current research, I feel like I’m also appropriating the culture of the dead—and I openly acknowledge that.

To counterbalance archaeology’s (and arguably artistic intervention’s) inherently extractive nature, I deliberately incorporate ritual technologies—such as joss paper, incense, and symbolic ritual offerings—in a subtle and poetic manner. These serve both as artistic methods and as gestures of tribute to the dead. I am also very sensitive to anonymity. I intentionally avoid addressing any specific ghost, tomb owner, or historical figure directly, thereby reducing the risk of appropriating a specific person’s narrative or identity. The speculative archaeologist is also an anonymous figure. Through this anonymity, my artistic intervention proposes a more general mechanism of repatriation and negotiation. To me, each project is more like a case study.

This cliff tomb project is particularly sensitive because I did enter two tombs whose owners remain unknown even to professional archaeologists. My entry was uninvited, without permission—neither from the local authorities nor from the tomb owners. I kept wondering whether I relate more to a grave robber than to an archaeologist. These sensitivities have become the core of the project. I keep asking myself: if the tomb owners were invited to my work, how might they feel? How can I honor them without causing offense?

What does trespassing mean to you in this context? It’s an act of transgression, an act of care? As a way of doing things in your work?

In this context, trespassing carries both literal and metaphorical meanings. Literally, it involves entering a physical space specifically designed for the dead. Metaphorically, it speaks to the blurred boundary between the realms of the living and the dead—a symbolic exchange that is constantly at play.

For example, in Chinese culture, burning joss paper (often referred to as ancestral money) represents a literal economic exchange—a kind of spiritual bank transfer from the living to ancestors in the afterlife. Beyond just money, this includes symbolic paper replicas of modern luxuries such as cars and smartphones. To me, this is not merely a practice of mourning or consolation; it opens up a speculative space for thinking about the ongoing economic and symbolic exchanges between the two realms. In that sense, practices like ancestral worship—alongside countless accounts of ghost hauntings—suggest that trespassing between realms has always existed.

My artistic speculation is that archaeology has the potential to evolve into a conscious and ethical practice—one that acknowledges, or even facilitates, symbolic exchange rather than ‘killing’ the spirit by sealing artifacts behind glass cases in museums. One potential site I’ve begun to speculate on as a “portal” is the archive room within archaeological institutions—ironically, a space I’ve personally struggled to access. The working title of my current project is Permission to Trespass. I aim to foreground the contradictions and tensions involved in negotiating access to the space of the dead.